Beachcombing is a fascinating and soothing mindful activity that involves exploring the shoreline in search of treasure such as driftwood, fossils, sea creatures, interesting pebbles, sea glass, animal footprints, sea weed and so on.

Beaches can be very specific in what they collect, because currents, weather conditions, geography and offshore habitats will all influence what lands on shore. Some beaches are good for driftwood or fossils, others for mermaid’s purses or sea glass. Visiting a beach after a storm is one of the best times for beachcombing as it can often result in an array of interesting finds being washed ashore.

Here is our expert guide to beachcombing, including things to look out for, how to beachcomb responsibly and legally, and the best beaches for beachcombing in the UK.

Plus, while you’re beachcombing, why not do a two-minute beach clean?

What is beachcombing?

Beachcombing is a soothing activity that involves combing the shoreline to see what objects of interest you can see. This could be shells, pebbles, seaglass or one of the seashore marvels listed below.

Beachcombing guidelines

- Don’t be greedy – collect natural things sparingly, as they provide food and shelter for strandline creatures.

- Stay safe – always check tide times and the weather forecast – and bring a mobile phone with you.

- Pick up litter – take a couple of minutes to remove any man-made litter that poses a hazard to the local wildlife.

Things to look out for on the beach

1

Acorn barnacles

Abundant on our rocky shores, acorn barnacles lead extraordinary lives. Once the drifting larva finds somewhere suitable to settle, it cements itself headfirst to the surface, builds walls and a trapdoor, and at high tide delicate, feathery limbs emerge from their apertures to sweep the water for food.

British seashell guide: how to identify and where to find

Britain’s seashores are littered with the shells of bivalves and gastropods. Enhance your next beach walk with our guide to some of the most common seashells found along the British coastline.

2

Mermaid's purse (dogfish case)

Also known as a dogfish case, a mermaid's purse is generally the eggcase of a dogfish or small-spotted catshark, our most common shark. If the egg is successful, the purse will no longer contain a yolk but instead is filled by a curled-up pup that eventually emerges through a slit at the top (some species, such as the rare white skate, take up to 15 months to hatch). Usually, beachcombers will find empty purses, where the fish has already hatched and is living in the sea. Some eggcases may contain dead embryos that possibly died from lack of oxygen after being stranded on the beach.

3

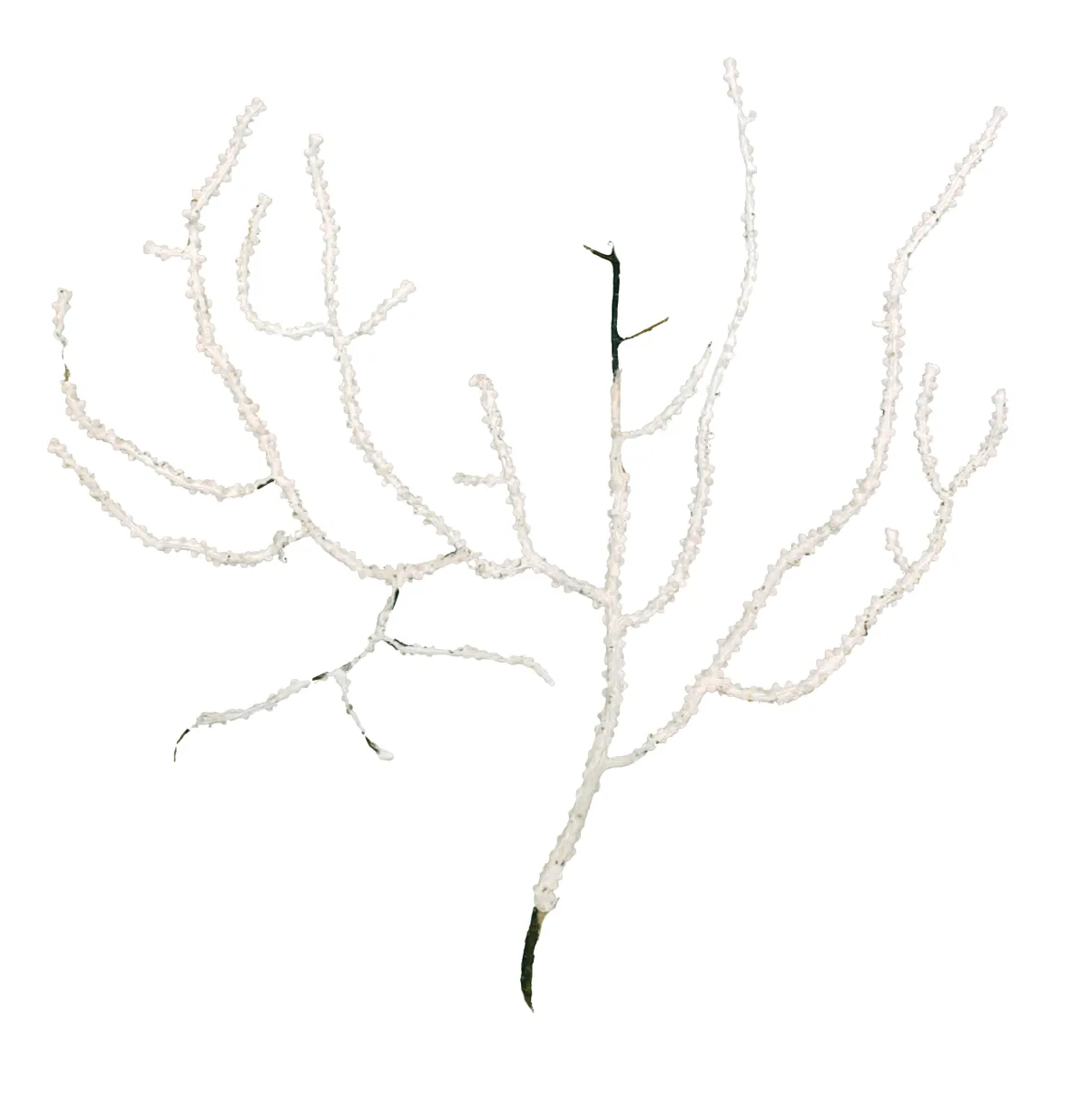

Pink sea fan

Keep an eye out for the skeletons of pink sea fans, or warty gorgonians. They turn up tangled among the balls of fishing line and other debris that litters our beaches. They’re ‘horny corals’ and despite their plant-like appearance, are actually animals. When washed up, the chalky outer layer, originally pink-orange, has usually worn away. When they’re alive underwater, anemone-like polyps emerge from warty bumps on the branches and wave tentacles to catch drifting plankton.

4

Piddock holes

If you look deep inside many clay pebbles, you might spot the white shell-tips of a piddock. This ‘boring mollusc’ drills holes with the toothed front of its elegant shells, drawing in water to increase pressure. Never able to leave its burrow, it is bioluminescent, which is unusual for a mollusc. The Romans used to eat them raw and, in 77AD, Pliny the Elder wrote that piddocks “shine as if with fire in dark places, even in the mouths of persons eating them”.

5

Keelworm tubes

Keelworm tubes are the chalky white scrawl often seen on washed-up pebbles, shells and fishing gear. Like the barnacles, each tube has an aperture and at high tide the tubeworms extend crowns of elegant, often colourful tentacles to feed. They are sedentary and unable to leave their tubes, but gregarious, as the larvae congregate to form colonies.

6

Red rags seaweed

One of the larger seaweeds, this red, rubbery seaweed is more commonly found along the south coast of England. As the red rags grow they form blades which eventually split.

7

Fish eye

Occasionally, you may spot a fish eyeball – often picked clean by gulls.

8

By-the-wind sailor

By-the-wind sailor often have blue, jelly-like base and tentacles, and on some the sail, too, is rimmed with iridescent blue. Each tiny sailboat, no more than an inch high, is actually a colony of hydroids. They live in vast flotillas on the open ocean and the blue pigment protects them from the sun.

9

Common whelk eggcase

Another eggcase that survives long after hatching is the common whelk eggcase. These form when whelks gather to spawn. Each small capsule contains hundreds of eggs, although the first whelk to hatch in each pouch then eats the rest. When the eggcases are yellow, they often contain live whelks. Another name for the eggcases is ‘sea wash balls’, as sailors once used them for washing.

10

Sea grapes (cuttlefish eggs)

Sea grapes sometimes wash ashore in spring and summer. These near-black spheres are cuttlefish eggs, stained with sepia – their mother’s ink (and also the name of this species of cuttlefish, Sepia officinalis). It’s the same ink that Leonardo da Vinci used to jot down ideas in his notebooks. Occasionally an egg misses the inking and it’s possible to see the tiny white cuttlefish growing inside.

11

Mermaid's purse (cuckoo ray eggcase)

The dark, horned mermaid’s purses are the eggcases of skates and rays. They all differ slightly depending on which species laid them. The Shark Trust, which runs The Great Eggcase Hunt, has some really useful resources online to help identify any you encounter and recording your finds on their website can help locate possible nursery grounds and contribute to shark conservation.

12

Skulls and bones

Skulls and bones can by trickier to identify. This slender, elegant one below is a guillemot skull.

How to go beachcombing

Best kit to take beachcombing

Take a tide table, bags for finds, a camera, wellies and warm clothes. A penknife, hand lens, specimen pots and anti-bacterial hand gel are also useful.

A good book for help identifying finds is handy. The Essential Guide to Beachcombing and the Strandline by Steve Trewhella and Julie Hatcher is particularly useful.

When is the best time to go beachcombing?

Any time is fine, but there are usually richer pickings after storms.

Where is the best place for beachcombing?

As Britain’s prevailing winds are from the south-west, the UK's west-facing beaches are often particularly good.

How to beachcomb responsibly

Under the Coast Protection Act 1949, it is unlawful to take any natural materials from any beach in the UK, including sand and pebbles. While it isn't illegal to take driftwood or seashells, many beaches discourage the collecting of these materials as they provide an essential habitat for wildlife and form an important part of the coastal ecosystem.

Best British beaches for beachcombing

Durdle Door, Dorset

This natural wonder soars out of the cliffs like a dinosaur curled around a stretch of beach and wonderfully clear water. The whole of the Jurassic coast is popular for fossil hunting, but as the site is a World Heritage site, it is important not to take what you find.

Reach Durdle Door via a short walk along the South West Coast Path. West Lulworth, Dorset, BH20 5PU.

Herne Bay, Kent

Visitors from across Europe flock to Herne Bay to search the fossiliferous beds. Shark teeth, mostly belonging to the Stratiolamia macrota, are the most prevalent type of fossil found. For the best chance of finding natural treasures amongst the sediment, head to the beach at Beltinge just east of Herne Bay, and walk further east towards Reculver. Visit during spring tides when water levels are extremely low, allowing visitors to search a wider area of the shoreline.

Redcar, North Yorkshire

The ease of access, café and proximity to town make Redcar the ideal location for young fossil collectors. The absence of cliffs and crashing waves also makes this a relatively safe environment for little ones to run about on, while the shingle surface means it’s easy to spot ancient shells on the surface. Although the nature of the environment here means that discoveries might not be particularly exciting for the more experienced collector, the bountiful numbers of bivalves washing up on the shore will excite new collectors both young and old.