Gritsone is as brutal as it is delicate. When blasting through the Pennines at Standedge 200 years ago to create the longest, highest and deepest canal tunnel in Britain, it was the hardness of the gritstone that took the project way over time, over budget and racked up a death toll of more than 50.

And yet, just beneath the surface, it is an incredibly delicate siliceous sandstone. Diligent rock climbers won’t go on it when it’s wet for fear of eroding the surface. After all, it is ultimately water that erodes this planet.

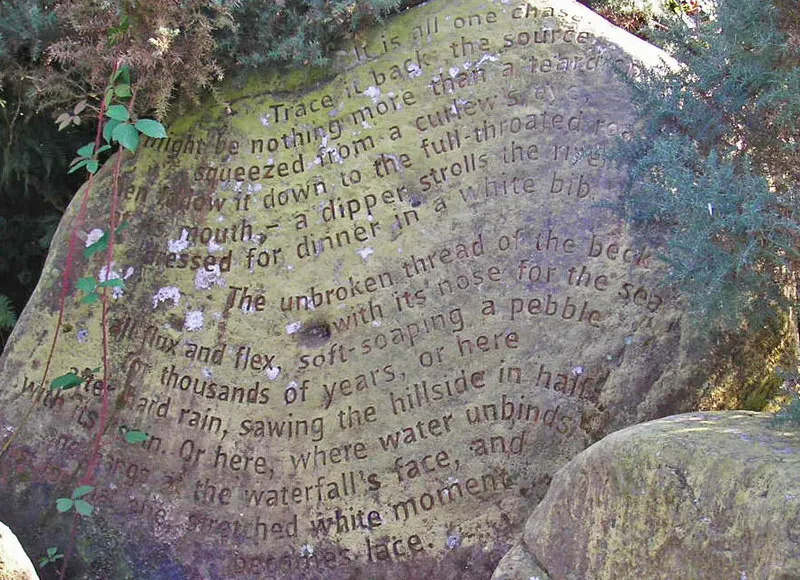

In West Yorkshire, this geological truism is laid out in poetic art: a series of gritstones carved with verse about water, the Stanza Stones. Poetry can often feel inaccessible and haughty. But Simon Armitage is a man whose words hit you between the eyes. You only need to look up his poem In Avondale – about a mother during World War One who saw eight of her sons go off to fight, and received letters through her door that five were not to return – to feel moved by his work.

Out on the Pennines are six of his works, gouged in the geology. There is even said to be a secret seventh stone out there. They are positioned to take advantage of the views: Rain faces out to the Irish Sea, Dew borders the dark edge of a forest and Mist sits atop the land that inspired the Brontë sisters and Ted Hughes.

Nature's sculptor

Water shapes our world and nearly every aspect of our lives, and for Simon, it felt like the right theme on the moor: “The way it has sculpted and morphed the landscape and driven the industries and the way it gets into our bones. We’ve all got rheumatism and we moan about it quite a lot.”

We climbed the Stanza Stones trail on the coldest working day I can remember, in a blizzard. We were a lean crew with no spare hands to bring asks or snacks along and we were out on the moor for nine hours. The blizzard had an irritating knack of abating just when the camera turned over, so we’d trudge several miles in horizontal snow then film with a thin sun cutting through the grey, denying us the sympathy we wanted in the aftermath.

Eventually, we came to the poetry seat, a stone bench with a view and a metal postbox inviting people to feed it a poem and receive a poem from the box in return. Mine had been laid up from Simon: “Get a move on, you’re not finished yet."

MOTIVATING VERSE

One of the aims of the Stanza Stones was to inspire other writers. On the poetry seat, we met Poppy Turner, a young poet who wrote about the moor for a national competition in order to become published. In her yellow knitted cardigan and Dr Martens, she was also feeling the pinch of the brutal weather and the time-eating-faff of filming, and was bordering hyperthermia by the time we’d finished. Nevertheless, Poppy’s feeling for the moor was clear in her verse, which she wrote after moving away to London:

Learning to Love You (Ode to the Yorkshire Moors)

Instead of braving the gradients

I was content to grow restless in the valley

Awaiting my escape into the big, busy world.

But despite myself, I miss you.

I miss the unforgiving wilderness

And the wind shocking the

pink into my cheeks

You’re wild and wily, you got deep under my skin

And like a nagging itching feeling, you’re calling me home

These words by Simon on a winter’s breath, faintly evaporating to slowly erode the stones holding their messages: “for thousands of years, people have been coming up into these wild places and expressing their desires and ideas through carvings to an audience of the wind, the gods and the sheep”.

The Stanza Stones whisper a reply to many who have been here before us.