It is more than 40 years since the remarkable ‘long hot summer’ of 1976, when Britain briefly experienced a Mediterranean-style climate, some places ran out of water, many more nearly did, and ladybirds abounded. It was a deeply memorable if challenging experience that had a profound impact on wildlife and habitats, both positive and negative.

We have had good summers since, notably during the mid-1990s, but none with the prolonged intensity of 1976, though 1989 shadowed it. Imagine five months of spring and summer with the weather set continuously fair; such was 1976 – day after day, week after week, glorious.

Why did the great drought happen?

The roots of the great drought of 1976 run deep. A paper published in Nature that year by two Met Office scientists states that rainfall in England and Wales in the period 1971-1975 was the lowest for any five-year period since the 1850s. Also, the period from May 1975 to August 1976 was the driest since records began in 1717. The two meteorologists view all this as constituting a once-in-500-year occurrence. (The 1995 summer was marginally drier but ground water supplies were in a more robust state.)

During the winter of 1974-75, the jet stream that dictates our weather shifted to north of the Hebrides, where it stayed for much of 1975. In 1976 it moved near Iceland – about as far north as it can go. All Western Europe was affected by drought – at one point there was real concern that it would lead to economic meltdown in France.

The drought itself developed over a period of many months, for the summer of 1975 was warm, dry and sunny, particularly from late July. It led into a relatively dry autumn and a mild and rainless winter. At winter’s end, most reservoirs in England and Wales were scarcely half full, one in Northamptonshire was almost empty. The preceding 11 months had been the driest on record. Then the spring rains failed to materialise.

The dry spring of 1976

The spring of 1976 was strong, sure, unsullied and dry. The vegetation hardly grew. Consequently, celandines and then dandelions rioted along verges and in meadows, especially where the grasses had browned off during the previous summer. Their flowerings provided a long period of goldenness that foretold the glory of the summer that was to come.

Which species thrived during the heatwave?

Warmth-loving insects abounded, their populations incrementally building up as first spring and then summer blossomed. Insect-feeding birds were well supplied with food.

The main losers during this epic spring were the frogs, newts and toads, as many of their breeding pools dried up. Badgers and moles struggled to find earthworms, which had retreated deep into the dry earth. Blackbirds laboured to feed their young, and house martins had to search far and wide to find mud for nest building. Generally, though, this was a good bird breeding season, with food plentiful and no adverse weather events.

When was the drought declared in Britain in 1976?

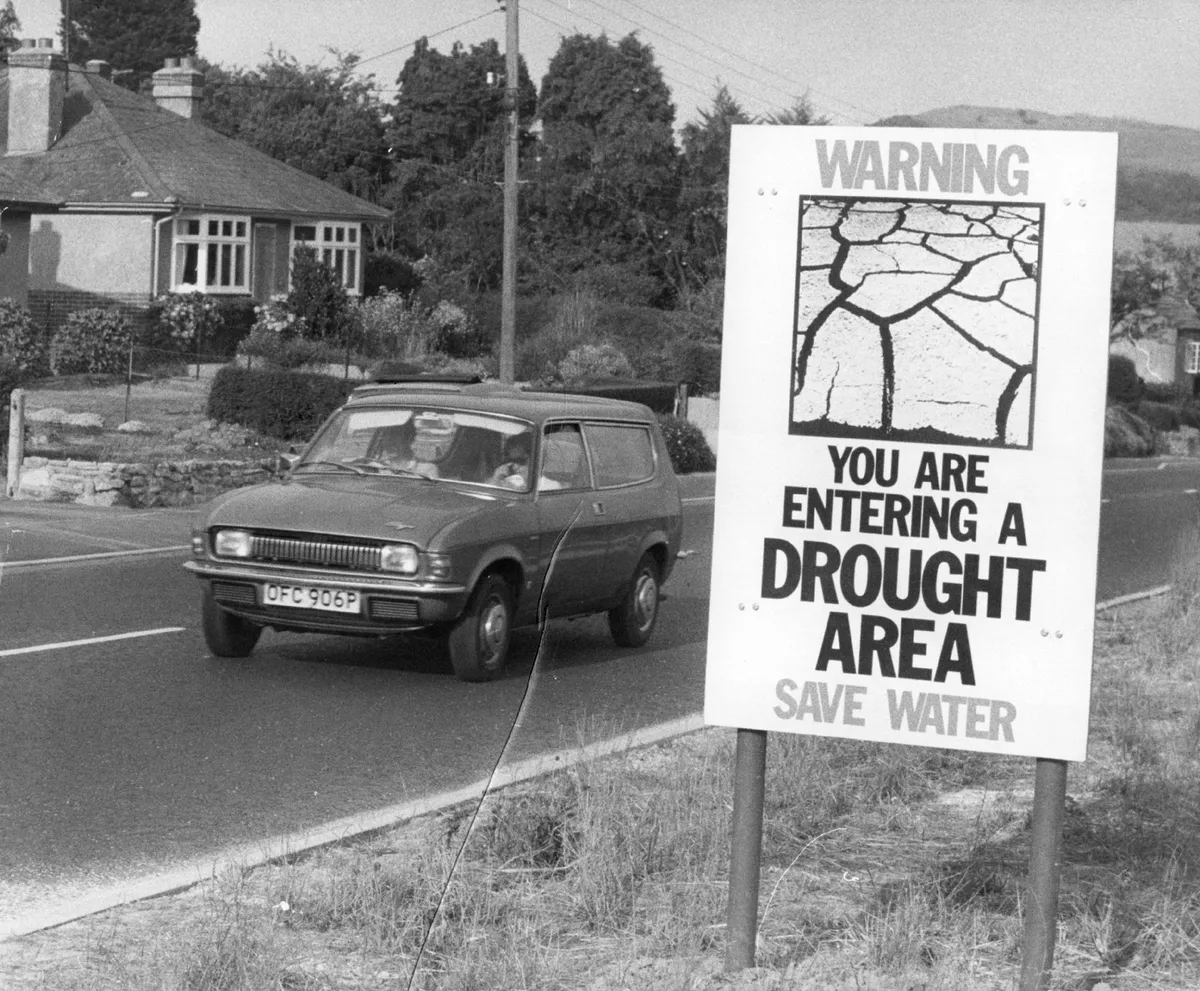

June bumbled along pleasantly. Then, around Midsummer Day, the weather entered a new dimension, as a searing sun burnt away almost all vestige of cloud. By the start of July, water rationing became inevitable and an emergency powers bill was announced on 3 July 1976. The resultant Drought Act came into force on 6 August. Besides banning hosepipes, the Act had serious emergency powers to reduce or turn off domestic and industrial supplies.

How serious was the 1976 drought for Britain?

Fortunately, the most extreme measures were never implemented, although in south east Wales, where the Brecon reservoirs dried up, the mains water supply was switched off for up to 17 hours a day.

East Anglia, the East Midlands, South Yorkshire and Devon were also severely affected. Standpipes (outdoor taps installed on streets to dispense water) were in use in many districts, one for every 20 houses. By late August, London had 90 days’ supply left, Leeds only 80. The slogan “Save Water, Bath with a Friend” appeared everywhere, and was wondrously lampooned.

Reservoirs, lakes, ponds and wetlands dried up – even some sections of rivers, exacerbated by extraction for human use. Fish perished in their thousands, and many birds died of botulism, as disease built up in stagnant, de-oxygenated and nutrient-enriched water.

What was the impact for farmers?

Farms struggled, for many were not connected to mains water supplies and their bore holes dried out. Strawberry crops shot over in the heat, while maize, cauliflower and sprouts failed altogether. The cereal harvest was modest, especially in eastern England where the grain failed to swell. The grass stopped growing, then browned off so that farmers had to feed barley straw and hay to hungry stock, while providing thirsty animals with water became increasingly nightmarish.

In East Anglia, and locally elsewhere, fields became so arid that the topsoil blew away on stiff easterly winds. Then, to add insult to injury, the autumn became so wet that much of the potato crop had to be left in the ground.

Heath and forest fires

It was a year of spectacular pyrotechnics, for one by one our heaths and moors went up in smoke, not always by accident. Road verge and railway line fires were commonplace, caused by discarded cigarettes, at times spreading into adjacent fields. Often the smoke rose almost vertically before hitting a high level wind, bending, and drifting horizontally. From midsummer, wildfire became a national preoccupation. The news was dominated by accounts of spectacular fires, on the Surrey heaths and the North Yorkshire Moors.

All told, between April and August over half the Surrey heaths went up in smoke, the largest being a 480-hectare block of the Pirbright Commons. Some fires were allowed to run, at least up to bulldozed firebreaks, due to the lack of water. The damage on mineral soils proved to be largely superficial but long-term ecological damage occurred on peatlands where the peat ignited.

Forest fires were rife too, though these were largely confined to conifer plantations established over former heathland. Over 2,000 hectares of forest burnt up, while everywhere cohorts of newly planted trees died of drought. Many mature trees suffered from drought stress, mainly beech and silver birch. Additionally, thousands of elm trees succumbed to Dutch elm disease, as populations of the vector beetle boomed at a time when the elms were severely stressed by heat and drought.

Ladybird swarms

This was the summer of the great ladybird invasion. One observer, in Louth, Lincolnshire, recalls: “I remember seeing the greenfly and aphids drifting past the doors like green smoke. This went on for at least a couple of days. Then came the ladybirds!” They were tracking the aphids, on which ladybird adults and larvae feed. There are also accounts of light aircraft vanishing into ladybird swarms, seas covered in ladybirds, and combine harvesters jamming up with ladybirds and aphids.

The 1976 influx, which climaxed for a month from mid-July, probably engaged the British public more than any other wildlife event of modern times, for there was no avoiding the swarms. There are accounts of holidaymakers running from holiday beaches, for people had flocked to the coast, seeking cooling breezes.

The ladybirds were biting people, apparently. All the starving ladybirds were seeking, of course, was moisture and food. They were desperate.

Butterflies also abounded, their populations in orders of magnitude more numerous than what we see today. However, in places their caterpillar food plants desiccated in the heat, and populations later collapsed, notably during the miserably wet June of 1977.

The impact of the draught on urban areas

This was the summer when the London underground fulfilled its ambition to become hell-on-earth. Office culture was severely impeded, for this was before the development of efficient air conditioning systems and jackets and ties were still de rigour. At Wimbledon, where 400 spectators were treated for heat exhaustion on a single day, the stewards rebelled and removed their jackets. That privilege was also claimed by stewards at Henley Regatta.

The most remarkable casualty was Big Ben, which broke down in early August for the first and only time in its history – for three long weeks during which time stood still as the sun leered down. More predictably, trains caught fire, car radiators overheated, and miles of tarmac roads melted and remained viscous.

1976 was a year of extremes. But, most remarkable of all, no one mentioned the term climate change; it hadn’t been invented.