A colossal eddy that looks as if someone has just pulled the plug on the seas surrounding the Inner Hebrides, the Corryvreckan whirlpool is a freak of nature that spawns like a poisonous toad on a rising tide between the islands of Jura and Scarba.

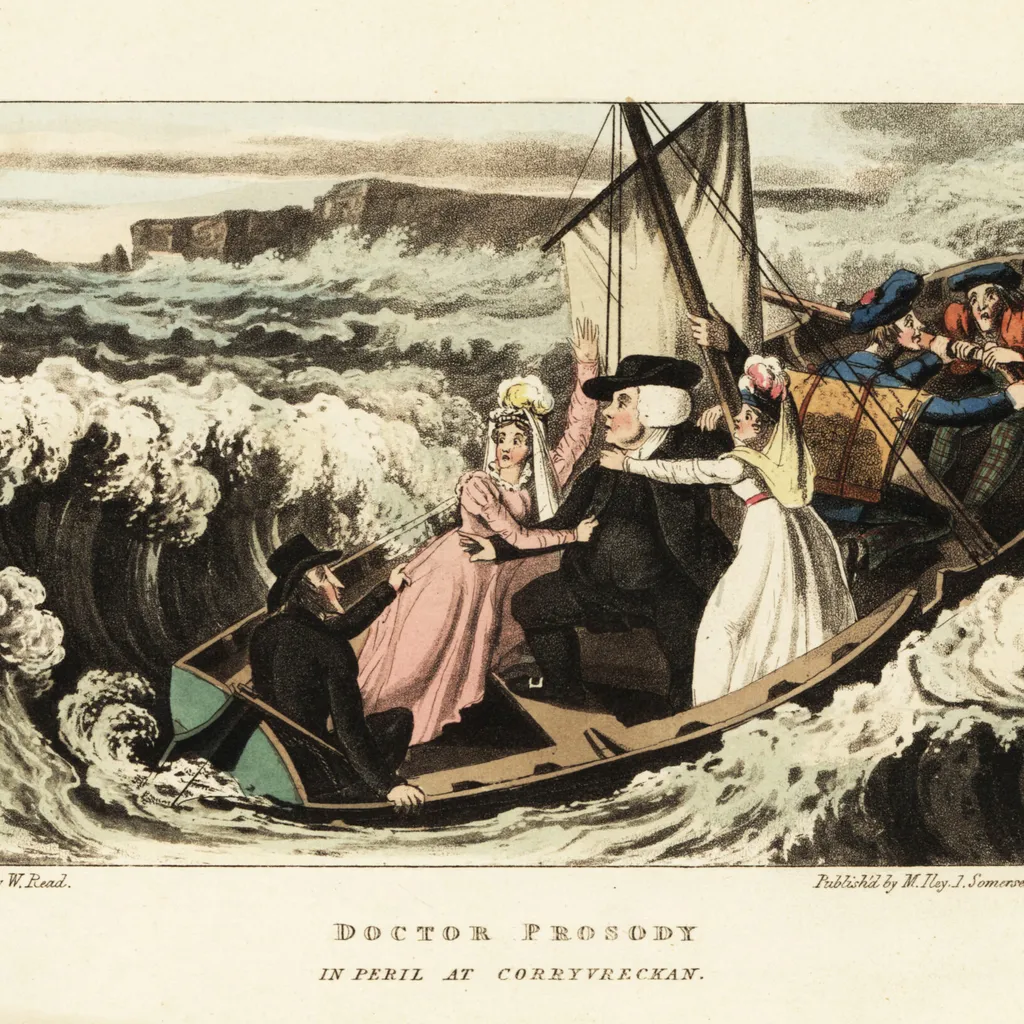

From the Norse king Breacan – who, legend has it, drowned in the whirlpool after trying to impress a local princess – to George Orwell’s entanglement with it in 1947 while he was living on Jura writing Nineteen Eighty-Four, the whirlpool holds a distinctive place in Scottish culture.

The nature writer Roger Deakin considered attempting to swim across the Gulf of Corryvreckan (the strait between the two islands) when he was writing his classic work Waterlog.

Approaching it on Jura, he describes in the book how he could hear the maelstrom before he saw it, sounding like “a low-pitched, continuous seething of brawling waves”. It was 300 metres offshore, and within its circumference was a “mêlée of struggling white breakers... headbutting one another”. Deakin backed out, saying an attempt would have been suicidal.

The first person known to have swum the Corryvreckan was, in fact, Orwell’s brother-in-law Bill Dunn, who had spent some time living on Jura. Smeared in sheep fat, he completed the swim in 1949, despite having only one leg. It took him about half an hour.

The Corryvreckan whirlpool is a freak of nature that spawns like a poisonous toad on a rising tide between the islands of Jura and Scarba.

Where is the Corryvreckan whirlpool?

If you want to see it for yourself, head to the west coast of Scotland between the islands of Jura and Scarba. The adventure tour group Swimtrek has run open-water swimming tours that take in a crossing between these islands. According to Swimtrek’s Jack Hudson (who has swum it himself), this can only be done safely at slack tide and when wind speeds are low. Even then, there are unusual currents that can be nerve-racking, he says. “If you jumped into the maelstrom at full force, you would be sucked down and disappear very quickly,” Jack says.

“People do massively underestimate the strength of maelstroms,” Jack adds ominously. “Captain Matthew Webb – the first swimmer to cross the English Channel – famously died trying to swim through a whirlpool under Niagara Falls.”

How does a whirpool form?

The Corryvreckan whirlpool forms thanks to the speed of the rushing tide, which races over a geologically complex seabed – comprising a depression of more than 200 metres and a pinnacle that rises to within 30 metres of the surface (illustrated right) – and through the narrow strait at nearly 16kph (8.5 knots). The Corryvreckan whirlpool is not a fixed entity. “It’s very difficult to pinpoint any one location where whirlpools occur,” Jack explains. “They are always scattered about by the intersecting currents.” Something that’s probably worth bearing in mind if you ever find yourself on Jura and feel in need of a dip.

Strong tides also create the conditions that lead to other famous whirlpools, such as the one in the strait of Saltstraumen near the Norwegian town of Bodø, which claims to have the world’s strongest tidal current, although there is no evidence it is the strongest.

Other notable ones include Old Sow off the east coast of the USA and the Naruto whirlpools, which appear in the strait between Shikoku and Awaji islands in southern Japan.

Though not featuring whirlpools, the Swinge Overfalls, off Alderney, the most northerly of the Channel Islands, are caused by strong tides sweeping over a rough seabed and are regarded as one of the most dangerous stretches of water in the UK. One sailor who attempted to cross them describes the waves in the overfalls as “enormous and very steep and short”; she says they lost almost all control of their boat while they were in them.

The Severn Bore and other tidal phenomenon

As it happens, the British Isles are a great place to live for anyone who enjoys phenomena that owe their existence to tides. The Severn Bore is well-known as one of the most remarkable examples of a tidal surge travelling up a river. It’s so powerful and predictable that surfers regularly take it on, travelling miles upstream on the rolling, rollicking wave. They call themselves “The Muddy Brothers”, and they compete to ride the bore for the greatest distance – a record currently held by one Steve King, who managed to do it for 9.25 miles (nearly 15km) in 2006.

Then there’s the cruelly named Bitches (and Whelps) – a reef of rocks that stretches between the Pembrokeshire mainland in south-west Wales and Ramsey Island. The narrow strait funnels the water into a tidal stream that reaches nearly 16kph, but the rocks themselves act like a dam that increases the speed to 33kph and creates a weir as much as 1.5 metres high.

A famous tragedy occurred at the Bitches in 1910, when the local lifeboat was wrecked on the reef after rescuing a ship that had been dragging its anchor. Three crewmen died, and those who survived endured a miserable storm-battered night on the rocks. Today, the Bitches are popular with kayakers and thrill-seekers taking power-boat rides from the small harbour of St Justinian’s.

Disaster in the bay

More recently, the incoming tide was responsible for the tragedy of Morecambe Bay in 2004, when 21 Chinese cockle-pickers drowned after being caught by the flood some 4km off Bolton-le-Sands. The tidal range – the difference between low and high tide – can be as much as 10 metres, and it can go out as much as 12km.

The idea that the tide at Morecambe Bay can race in at speeds faster than a galloping horse may be fanciful, but – following the 2004 tragedy – a coastguard was quoted in The Scotsman as saying it’s faster than a person can run. “The seawater that surges up gullies between sand ridges can easily cut people off,” the coastguard said.

If all this sounds a bit alarming, there are gentler alternatives. The Bantham Swoosh, an annual 6km organised swim in South Devon, is timed so you arrive at the mouth of the River Avon at the peak of the ebb tide that is racing along at 8km an hour. Kath Broomfield, a speech therapist from Gloucestershire who took part in the swoosh in 2018, said it felt like she’d “been scooped up by an inflatable armchair on wheels that was being simultaneously pushed and spun round”.

Still too much? How about Northey Island in the River Blackwater in Essex. Here, saltmarsh was reclaimed from the sea in the 18th century, but the wall has been subsequently breached, and at high tide you can now sail inside the island. The causeway at the southern end of the island appears at low tide and was the location of the Battle of Maldon in 991, when Danish invaders slaughtered the local Anglo-Saxons. The story goes the English were only defeated after they allowed their Viking foes to wade across the river, failing to attack them when they were vulnerable.

Tidal win for wildlife

The strong tides all around the British Isles are one of the reasons hundreds of thousands of waders and wildfowl arrive here in autumn to overwinter. The tides haul billions of tonnes of seawater off our shores, exposing at low tide more than 1,000 square miles of inter-tidal mudflats around the UK’s shores.

The mudflats of the Bristol Channel and River Severn, the Solway Firth and the River Humber – among many others – provide rich feeding grounds for birds, where they can fatten up after long migrations (for many) from Arctic Russia or Svalbard on the abundance of juicy invertebrate morsels.

Saltmarshes – which are created where low-lying land is covered and then uncovered by tidal waters – act as nurseries for fish and other marine wildlife, while also being excellent carbon sinks. Scientists estimate that they sequester carbon at between two and four times the rate of mature tropical forests.

Thrust out as it is into the eastern reaches of the Atlantic Ocean, the archipelago of over 6,000 islands that make up the British Isles is a perfect place for tidal phenomena, which must be endured by those who work in them but enjoyed by many others. Do take some time to do so yourself – but always remember your tide table.

How to experience the Corryvreckan whirlpool

A number of operators run boat trips that will take you up to (but hopefully not into) the Corryvreckan whirlpool.

- To the north of Scarba, Seafari Adventures is based on the island of Easdale and does whirlpool and wildlife-focused expeditions into the gulf. seafari.co.uk

- Jenny Wren Boat Charter is located on the mainland at Craobh Haven Marina, opposite the Isle of Shuna. It does the whirlpool, wildlife and whisky – though not necessarily all on the same trip. jennywrenboatcharter.com

- Jura Boat Tours runs three-hour trips from Craighouse on Jura. juraboattours.co.uk

Alternatively, do what Roger Deakin did and travel to the north coast of Jura to watch the Corryvreckan from the safety of dry land.

How does the moon influence the tides?

- Earth and the Moon exert a gravitational pull on each other. The Moon’s pull causes the oceans to bulge on both the side closest to the Moon and on the opposite side as well; the bulges create the high tides.

- Those parts of the Earth at 90˚ to the Moon are where the low tides occur. As the Earth rotates over the course of 24 hours, the areas of high tide shift, too. But the tides are also affected by other factors, such as the shape of the Earth (it’s not a perfect sphere), the continents and the depth of water.

- Twice a month, the Sun and Moon line up, exerting a stronger gravitational pull and bigger tides, known as spring tides. They create higher highs and lower lows. When the Moon and Sun are at right angles to each other, the pull is reduced, resulting in smaller tides, called neaps.

Want to find out more?

Listen to our podcast about the Severn Bore, or check out our collection of features about the magnificent Highlands and all it has to offer.