The Lake District and Yorkshire Dales National Parks are expanding – and the good news is that you can explore the prettiest parts of the new extensions in one fabulous walking weekend.

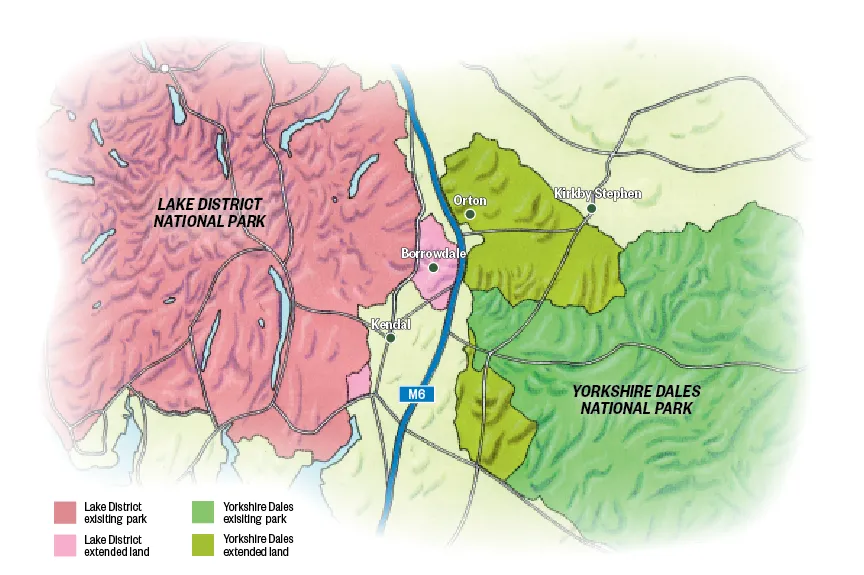

From 1 August, the two national parks will virtually touch each other, separated only by the tarmac ribbon of the M6 motorway. The extensions increase the size of the two parks by a combined area of almost 518km², creating a continuous swathe of protected upland landscapes covering some 4,500km² in total.

This is no reluctant merger or hostile takeover. Rather, their closer proximity creates starker contrasts between them and brings the differences in the landscape, geology, culture and heritage of these two great parks into even sharper relief.

To the west of the boundary lie the foothills of the Lake District fells and the tranquil roadless valley of Borrowdale, which will sound familiar to Lakeland lovers but is a world away from its more famous namesake. To the northeast, the stark limestone plateau of Great Asby Scar, which rivals anything in Yorkshire Three Peaks country yet attracts a fraction of the tourist footfall. And between the two, the pretty little village of Orton, with its friendly inn, cafés and an artisan chocolatiers, makes the perfect base from which to explore these two hidden gems.

Why these stunning enclaves weren’t included in their respective parks’ original boundaries in the 1950s has been the subject of much debate, but the oversight is about to be remedied. The upside is that they’re yet to be discovered by walkers oblivious to their charms, so why not make a beeline for them before the secret gets out…

Bewitching borrowdale

Perhaps the most intimate and enchanting of the Lakeland dales are those without roads – Ennerdale, Mungrisdale, the Newlands Valley and, from August, Borrowdale. Alfred Wainwright described Borrowdale as the prettiest valley in Westmorland outside the Lake District and, thanks to sterling work by the Friends of the Lake District – which was instrumental in getting the park boundaries redrawn – the valley has grown still prettier. Friends’ volunteers have restored the landscape to more closely resemble how it would have looked in the 19th century, rebuilding barns and dry stone walls and establishing two natural wildflower meadows on the valley floor.

Enter the valley from its eastern end, where the beck from which it derives its name empties into the spectacular Lune Gorge, and the background roar from the M6 and West Coast mainline quickly subsides. The track strikes out west alongside the beck, initially through woodland, then meandering round to the north and opening into a natural basin flanked by 450m-high hills.

In summer, the pristine plunge pools and sparkling cascades of the Borrow Beck are a splendid place for a dip but today, with a cool breeze blowing and slate-grey clouds barrelling across the valley threatening sleet, the frigid waters are less inviting.

Under a bridge, smooth pebbles glisten like gems on the riverbed and the bedrock has been sculpted into organic shapes by the swirls and eddies of the beck over countless millennia. Above the bridge, the valley swings round to the northwest and opens out. In summer, High Borrowdale’s traditional meadows burst into a riot of colour as wildflowers bloom. But today, the flanks of the fells that cradle this upland plain are wearing their drab winter cloak.

Briefly, when a watery sun bursts through the swirling cloud, for a few seconds the valley shows its true colours:

a patchwork of muted green winter grass, rusty stands of bracken and darker patches of heather. But this evanescent interlude is soon forgotten as another shower barrels down the dale.

The path continues along the valley floor to the western reaches of Borrowdale, which extend beyond the A6 and across the old national park boundary. To enjoy stunning views of the southern fells and beyond, the steep climb up onto the ridge at Ashtead Fell unlocks huge vistas to the south and west.

It’s possible to trace a route back to the starting point via the series of summits extending southwest, but this high-level route is occasionally trackless and tough-going in places, so should really only be attempted in ideal weather. Energetic souls who do reach the ridge will also be rewarded with striking views up to the northeast, where a great pale scar slashes through the grassy pastures beyond the Lune valley. This is the objective for tomorrow…

Gritty Great Asby Scar

Above the village of Orton, the ground rises steeply in a series of terraces to a striking plateau where a lattice-work of limestone pavements breaks through the velvet sward. The contrast with the intimate, sheltered sanctuary of Borrowdale, just a few miles to the southwest, couldn’t be more pronounced.

The scar is stark and appears featureless, save for the impossibly intricate mosaic of clints and grikes stretching, fractal-like, for miles out to the edges of this exposed plateau. But look closer and the limestone is shot through with fossil remains, while the gaps between shelter delicate ferns and, in spring and summer, a huge variety of rare orchids.

The features in the landscape are equally stark: the occasional wind-blasted tree, clinging with twisted boughs and contorted roots to the sparse soil lodged in the deeper fissures etched into the limestone. Ravens soar and swoop on the updrafts above the escarpment, cawing indignantly at anyone with the temerity to trespass on their rocky eyries, while Persil-white sheep graze contentedly among the outcrops, cropping the grass to a suede-like sward.

The pavements and terraces up here are criss-crossed with paths and, while there are a number of circular walks from Orton, sometimes it’s best simply to wander around with no particular route in mind.

On bright summer days, the sun reflects off the dazzling white limestone in all directions, casting an ethereal radiance across the plateau and picking out the vibrant pinks of the native orchids in high definition.

A path leads northeast out of the village up onto the plateau between Orton and Great Asby Scar or there’s a car park where the Appleby road crests the scar, with direct pedestrian access to it.

The stunted trees make obvious waymarkers, as do the memorial cross atop Beacon Hill and a sprinkling of cairns – a legacy of much earlier inhabitants. Standing at the highpoint of the plateau, Castle Folds is the site of Romano-British hillfort, whose fortified walls are still visible a couple of hundred yards northeast of the trig point.

And what a commanding vista this elevated stronghold offers: to the west, an epic widescreen view of the Lakeland fells; to the east, the colossal massif of Cross Fell and the North Pennines, including the almost perfect cone of Dufton Pike and the dramatic cleft of High Cup and to the south the voluptuous velveteen curves of the Howgills.

The best views of mountains are often from afar and, while this magical landscape has a captivating charm of its own, nowhere else in England provides such an epic panorama of the highest mountain ranges in the country. What better a place to celebrate the reconciliation of these two stunning landscapes with their estranged outposts than a vantage point that offers breathtaking views of both?

Mark Sutcliffe is a writer specialising in walking, landscapes and local produce. Inspired by Alfred Wainwright and Arthur Ransome, he spent his early years exploring the Lakes and the Dales.