Charles Dickens wrote these words to his friend Henry Adams in 1840. Find out just how Kent bewitched the great writer.

Born in Portsmouth, Hampshire on Friday 7 February 1812, Dickens spent his formative years in Kent. It was here he found inspiration for his greatest characters and settings for his works. Even after he and his family moved away to London, he chose to spend his holidays in the county.

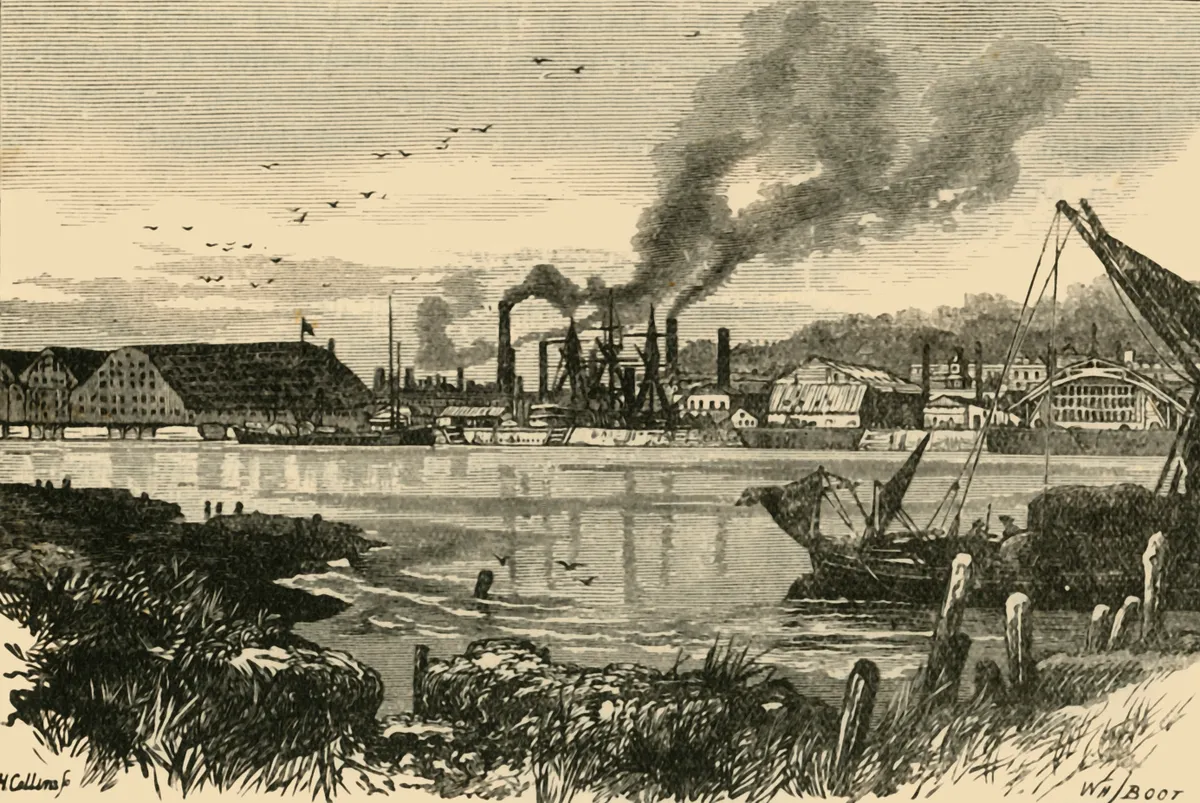

The great man’s first contact with Kent came when his father was posted to the naval dockyard at Chatham on the tidal River Medway in 1817. John Dickens (the inspiration for Mr Micawber in David Copperfield, 1850) worked in the Royal Navy Pay Office, which can still be seen in the historic town – find it marked with a plaque, adjacent to the Officers Terrace behind the Commissioners House. At the time, Chatham was the greatest dockyard of the days of sail. It was where HMS Victory was launched in 1765, and Dickens reported receiving “my earliest and most enduring impressions among barracks and soldiers, and ships and sailors”. (Where We Stopped Growing, 1858).

Charles looked back on his formative years in the Medway towns as among the happiest of his life. Many of the buildings of Rochester High Street, including the Guildhall, the Corn Exchange with its “moonfaced clock” and Restoration House (the model for Miss Havisham’s Satis House), are recognisable from their descriptions in

(1860). In addition, Eastgate House became the model for Westgate House in

(1837) and the Nuns House, “a seminary for young ladies” in

(1870).

The Dickens family home at 11 Ordnance Terrace can still be seen on a quiet road above Chatham station, which, during Dickens’ childhood, was an area of fields overlooking St Mary’s church. He was dismayed to discover the fields replaced by the railway when he returned in later life.

In his first novel,

, Dickens drew on childhood memories as he described the view west from Rochester Bridge: “On either side, the banks of the Medway, covered with cornfields and pastures, with here and there a windmill, or a distant church, stretched away as far as the eye could see, presenting a rich and varied landscape, rendered more beautiful by the changing shadows which passed swiftly across it, as thin and half-formed clouds skimmed away in the light of the morning sun. The river, reflecting the clear blue of the sky, glistened and sparkled as it flowed noiselessly on; and the oars of the fishermen dipped into the water with a clear liquid sound, as their heavy but picturesque boats glided slowly down the stream.”

Today, the tidal Medway sees pleasure boats and the occasional barge plying its waters. You can find characterful cafés and shops in old Rochester, with its Norman castle and cathedral, or explore the fortifications and historic dockyard in Chatham, (which Dickens called Dullborough in

, 1859 and Mudfog in

, 1837).

Dickens later told his biographer, John Forster, that “the seven miles between Maidstone and Rochester is one of the most beautiful walks in all England” and proposed meeting at Paddock Wood, taking a trip on the Medway Valley railway to Maidstone, and returning to Rochester by way of the “druidical altar” at Kits Coty House, a journey still possible today.

And you can still enjoy the magnificent views from Bluebell Hill across the Medway Gap that Dickens described in a letter to his friend Captain Morgan in 1860: “I wish I could carry you off to a favourite spot of mine between this and Maidstone… We often take our lunch on a hillside there in the summer, and then I lay down on the grass – a splendid example of laziness.”

Today’s scene is still largely the same, with views stretching down across the Medway valley, over the ridge of Kentish ragstone that runs parallel with the downs (the great chalk backbone of Kent), towards the distant vale of the Weald of Kent beyond.

It was on one of many childhood jaunts with his father, in 1819, that Dickens first set eyes on Gad’s Hill Place, a Georgian country house built for a former Mayor of Rochester, above the Medway at Higham. Dickens resolved to own it one day; finally achieving that ambition on 14 March 1856.

Dickens paid extra for land opposite the house, and dug a tunnel beneath the road for convenience, which is still decorated with masks of tragedy and comedy he purchased in Italy. Here, in 1864, his Swiss chalet was erected, a gift from the actor Charles Fechter, now preserved in the grounds of Eastgate House in Rochester. He wrote in these inspiring surroundings until the day before his death. Not far away, Chalk, now virtually a suburb of Gravesend, was where Dickens honeymooned in 1836. The forge is the likely model for that of Joe Gargery in

.

While he lived at Gad’s Hill Place, Dickens enjoyed walking to local churches, with Chalk, Shorne, St Mary’s Higham (where his daughter Katey was married), and Cooling being particular favourites. Cooling can still be recognised from its description in the famous opening chapter of

: “a bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; …the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes…”

Nearby in Cobham, Dickens was a frequent patron of the Leather Bottle, a hostelry opposite the village church, featured in

.

When he lived at Higham, Dickens’ neighbour, the 6th Earl Darnley of Cobham Hall, gave him a key permitting a shortcut from Gad’s Hill Place across the park. Although some trees have gone, and the wildlife is less numerous, it remains recognisable from its description in

: “an open park with an ancient hall of Elizabeth’s time. Long vistas of stately oaks and elm trees appeared on every side; large herds of deer were cropping the lush grass; and occasionally a startled hare scoured along the ground.”

A little to the south, the rolling hills of the Kent Downs are perhaps the most accessible Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty in England. Little has changed here during the past two centuries, and Dickens would recognise the gentle slopes sheltering hidden valleys, dotted with oast houses, used for drying hops, and pretty villages such as Newnham and Chilham, where mellow cottages showcase local flints, timber weatherboarding, painted pargetting and traditional Kent peg tiles.

By contrast, the steep scarp slope on the south-west side hosts grassland that blazes with wildflowers and orchids in early summer, amid magnificent stands of beech and ancient yew, which cling to the slopes above the spring line. Here, the Pilgrims’ Way links villages and coaching inns at places such as Boxley, Lenham and Charing, like a string of pearls stretching all the way from the Surrey border near Westerham to Ashford and beyond.

Our next stop could be Faversham, where you can still find “the hotel [the Ship], forming one side of the queer little market square… immediately confronting the lop-sided little town hall, with its big-faced clock and its supporting pillars forming a little arcade, in which, probably, the merchants of Faversham do congregate.” (

, 1864). Canterbury, Kent’s capital and centre of pilgrimage since the murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket in 1170, features prominently in

. Dickens, like his fictional David, “sauntered through the dear old tranquil streets”, and “mingled with the shadows of the venerable gateways and churches”, saw “rooks sailing about the cathedral towers; and the towers themselves, overlooking many a long unaltered mile of the rich country and its pleasant streams.”

The Kings School Canterbury is thought to be the model for Dr Strong’s school, and you can still see the House of Agnes (Wickfield) in St Dunstan’s Street.

Across in Thanet, Ramsgate, with its royal harbour, is popular today for its marina and restaurants. It appears in Dickens’ early work

(1836) as a place where “the sea, dancing to its own music, rolled merrily in” and “crowds of people promenaded to and fro.”

Nearby Broadstairs (

) was immortalised by Dickens as

(1861), and he regularly escaped here from the heat of London to write most summers between 1837 and 1859.

In 1843, he described its charms to his American friend Professor Felton “This is a little fishing place; intensely quiet; built on a cliff, whereon – in the centre of a tiny semicircular bay – our house stands; the sea rolling up and dashing under

the windows.”

Dickens stayed at what is now the Royal Albion Hotel, and rented various houses locally, but his favourite was Fort House, which still overlooks Viking Bay. Close by is the home of Mary Pearson Strong, the model for Betsey Trotwood in

, which is now the Dickens House Museum.

As Broadstairs grew more popular, Dickens found that noise disturbed his concentration. He switched allegiance to Folkestone, now renowned for its contemporary art scene. In the summer of 1855, he wrote part of

(1855) at 3 Albion Villas, and later performed one of his earliest readings in a local builder’s saw mill. He often went for long walks along the cliffs to relieve the stress of writing, exclaiming in a letter, dated 1855, to fellow writer Wilkie Collins: “You know my state of mind as well as I do. How I work, how I walk, how I shut myself up, how I roll down hills and climb up cliffs; how the new story is everywhere, heaving on the sea, flying with the clouds, blowing in the wind; how I settle to nothing.”

On 9 June 1865, Dickens and Ellen (Nelly) Ternan, muse of his later years, were all involved in a train crash, on their way back from France, in the Kentish village of Staplehurst. It claimed 10 lives after the train was derailed at speed.

Dickens was writing his penultimate novel,

(1864), at the time, and was forced to return to the wreckage to rescue his manuscript, after helping to comfort the injured and dying. He was hailed a hero for his rescue efforts but firmly refused to write about it publicly, or attend the inquest. Afterwards, he became a changed man and gave up his lucrative reading tours due to ill health.

He retreated once again to write but died of a stroke, aged 58, exactly five years to the day after the Staplehurst accident, leaving the manuscript of

, unfinished. Before setting aside his pen for the last time, he wrote these words, demonstrating his lasting affection for the cities, towns and countryside of Kent: “A brilliant morning shines on the old city. Its antiquities and ruins are surpassingly beautiful, with a lusty ivy gleaming in the sun, and the rich trees waving in the balmy air. Changes of glorious light from moving boughs, songs of birds, scents from gardens, woods, and fields – or rather, from the one great cultivated island in its yielding time – penetrate into the Cathedral, subdue its earthy odour, and preach the Resurrection and the Life. The cold stone tombs of centuries ago grow warm; and flecks of brightness dart into the sternest marble corners of the building, fluttering there like wings.”

Portsmouth-born Charles moved with his family to Kent in 1817, leaving for London in 1822. His father was imprisoned for debt, and young Charles was sent to work in a blacking (boot polish) factory, an experience he never forgot.Teaching himself shorthand, he became a parliamentary reporter. He first found success writing , inspired by his Medway childhood, and started writing //The Pickwick Papers in 1836, the year he married Catherine Hogarth. They had 10 children.In all, Dickens wrote 15 novels. Much of , and are set in Kent. Shortly after buying Gad’s Hill Place, in 1857, he met actress Ellen Ternan, a relationship he managed to keep secret from the public, and separated from his wife. He died at Gads Hill Place and lies buried in Westminster Abbey. Discover more at www.dickens2012.org.