I had an unremarkable 1970s adolescence: tank-tops, lashings of prog rock; that sort of thing. Unfortunately, by the time I had it, it was the 1980s and all those fashions had been swept under the carpet of history.

But I didn’t care. I was too busy re-reading JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Today, with fantasy more entrenched than ever in the mainstream, Tolkien’s work is rightly taken seriously. Back then, though, the thought was absurd. That didn’t stop me, either: I was obsessed. Well, if you think trying to learn Elvish is a sign of obsession, that is.

Perhaps as a reaction to such excesses, I left Tolkien behind when I went to university, packed away with the rest of my childhood. And there he stayed until I became a father in my 30s and began to consider the books my children may enjoy.

Reading The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit again was a revelation. It seemed a different book, steeped in loss, shot through with a quiet dread of collective memory and its inevitable failure over long arcs of time. I was surprised to discover that one of the explicit aims of his work was to celebrate England.

On one level, that meant trying to reclaim what was left of pre-Conquest English language and culture and make it whole again, to create a rich and living mythology out of those scant remains that would finally redeem them from oblivion.

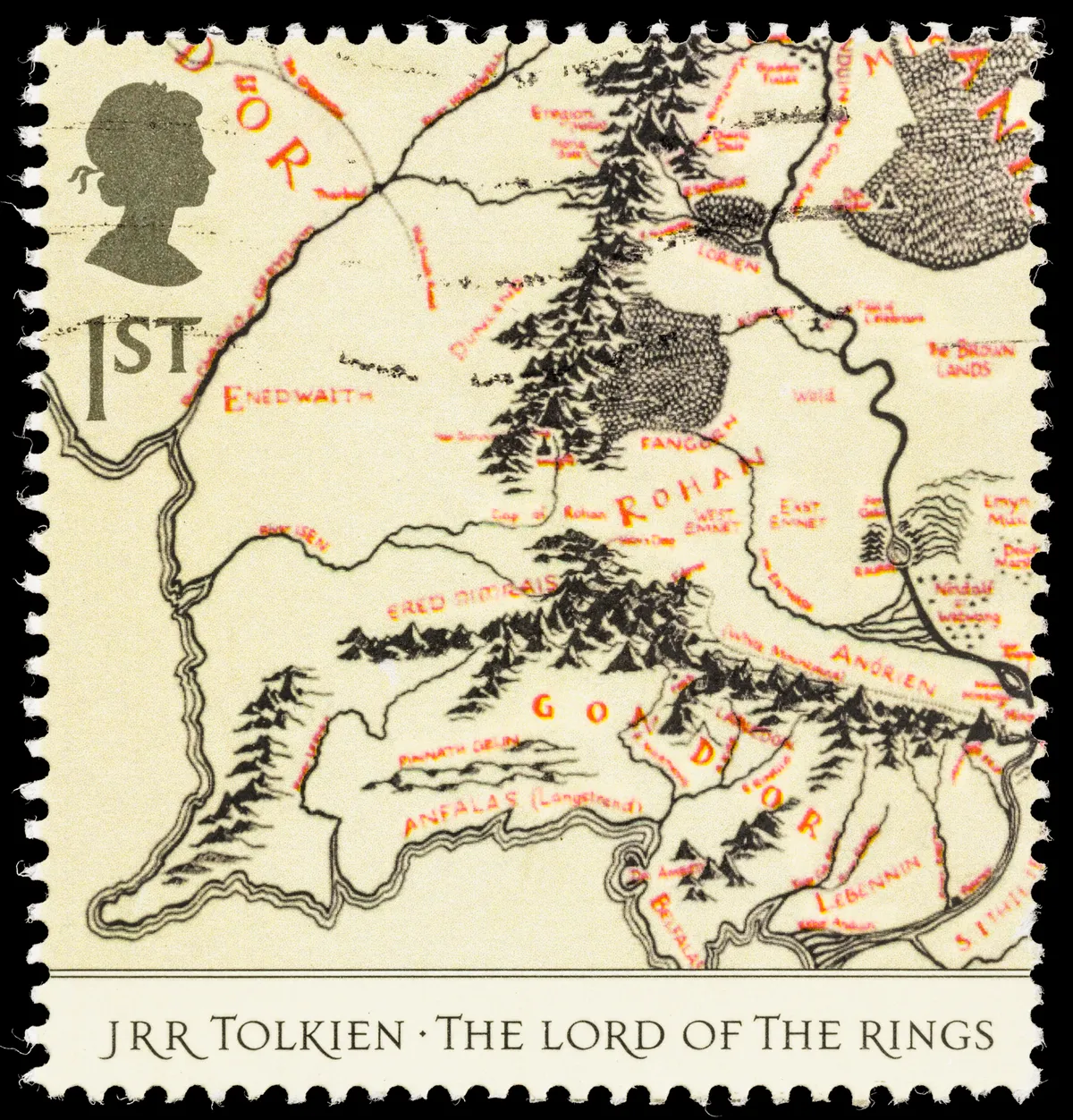

But on another level, that meant the landscape itself, and I decided to set out on a quest of my own to uncover Tolkien’s England and map, as far as possible, connections between Middle Earth and the countryside that he loved.

It would be a mistake to think this was divorced from Tolkien’s other aim, however: the obliteration of Anglo-Saxon and earlier cultures from English life has meant that much of what survives of these societies only does so in the woods and hills and rivers, in their names and in the folklore that surrounds them.

The search for Tolkien’s England, then, was also a search for the very things that so moved him: the last traces of lost peoples and their forgotten impress on their world.

Gondor in the Malverns

In Middle Earth, the border between the kingdoms of Rohan and Gondor is marked by the Ered Nimrais mountain range, known colloquially as the White Mountains. Tolkien peopled their past with the Dead Men of Dunharrow, cursed for betraying King Isildur at the end of the Second Age and doomed to live on as wraiths beneath the mountains, until Aragorn comes to redeem them. Before them came the primitive Púkel-men.

It’s a good example of the way Tolkien layered his work – and his landscapes – with a subtle sense of history and myth, mirroring his own preoccupation with language and loss. But his inspiration was a good deal less dramatic: the green and mist-soaked uplands of the Malvern Hills.

CS Lewis and Tolkien visited often in the 1930s, arriving on the early train from Oxford and spending the day amid the melancholic beauty of Malvern’s high furrowed slopes and ridges. Lewis, incidentally – who took walking a good deal more seriously than Tolkien – often found himself irritated at his friend’s evident dislike of exertion. Not for nothing did Tolkien make his Hobbits lazy.

Hobbit holes

Tolkien claimed that the idea of Hobbits came to him from nowhere as he sat marking exams in the early 1930s. Perhaps that is how he remembered it, but it seems unlikely to be true.

Just a few years before, in 1928, Tolkien had been invited to participate in an archaeological dig on the site of a Roman temple on what is now Camp Hill, Lydney Park, Gloucestershire. The extensive temple ruins sit in a bare ferny plateau on the top of a steep, wooded hill overlooking the Severn Estuary to the south. The slopes and ridges of the hillside are packed with plane trees descended from those the Romans brought to Britain.

The hill is studded with holes that local folklore has long said were the dwellings of a small race of people. It is not hard to see why when you see one – perhaps 60cm (2ft) high and 1.2m (4ft) feet across – with its entrance framed by stone posts and a cleanly cut lintel, and its location sheltered from the winds racing upriver.

The Shire

If the Hobbit holes are in Gloucestershire, the spiritual home of the Shire is to the north-east, in the Warwickshire countryside of Tolkien’s childhood as the 19th century folded into the 20th. Tolkien located it specifically in 1897, the year of Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, when he was just five.

The intensity with which Tolkien remembered this brief snatch of childhood is understandable. His father had died suddenly in February 1896 and his family had moved to Sarehole – a village outside Birmingham – that summer. Eight years later, his mother, too, was dead, and Tolkien’s country idyll was over. The next time he came here, in 1933, he was heartbroken at how it had been destroyed.

But that was the emotional reaction of a man who still mourned so much more than urban blight. For us, quite the reverse is true: it is surprising how much has survived. In particular there is Sarehole Mill, imported directly into the Shire as the mill in Hobbiton. Built around 1800, the mill is now a museum, with the gears, waterwheels and millstones that so fascinated Tolkien still intact. Outside, the millpond is calm; with the mill quiet now, its stillness attracts herons and kingfishers.

A mile away to the north of the mill is Moseley Bog, the inspiration for the Old Forest on the borders of the Shire. Indeed, as Tolkien’s first encounter with English woodland, it may also be the emotional basis for all the forests and woods of Middle Earth.

It is a small remnant of the forests that once spread across the island and archaeologists have found heat-shattered stones in the water that date to 1100BC, a reminder of the unknown people who lived here until the Celtic invasions erased them from history.

It has changed little since Tolkien played here. You walk down to the bog through hawthorn archways and the deeper you go towards the curled and knotted streams at its heart, the deeper are the shadows and dark spaces between the vine-shrouded trees. Tolkien may have revered trees and forests, but he understood and respected them, too. They were a direct connection to the lost England of his imagination.

The Ribble and the Shire border

Tolkien came north to the Ribble Valley several times during the Second World War to visit his son John, who was studying for the priesthood. Tolkien stayed at Stonyhurst College, one of England’s leading Catholic schools, in what is now the deputy master’s house.

He based Tom Bombadil’s house in the Old Forest on the college’s visitor’s lodge. Around a century old, the house is square and inviting, built of yellow-grey stone. It sits at the end of a muddy track no more than half-a-mile from the main school building, hedged by woodland.

The convergence of the Shire’s three rivers – the Brandywine, the Withywindle and the Shirebourn – maps exactly on to that of the Hodder, the Ribble and the Calder. The Shireburn Arms is the area’s best pub, and Tolkien liked pubs a lot.

Hacking Hall, a handsome Jacobean house on the green banks of the Hodder, is the probable source for Brandy Hall in Buckland, the more so when you discover that the Hodder was the ancient boundary between Lancashire and Yorkshire, as the Brandywine divides Buckland from the Shire. When Tolkien visited here there was a working ferry across the river, just as there is in The Lord of the Rings.

Bree and Sauron’s temple

Beyond the borders of the Shire, Bree – where the Hobbits first encounter humans – is based on the village of Brill in Buckinghamshire, not far from the old Roman road known as Akeman Street.

The name Brill is a contraction of Bree Hill, from the Celtic ‘bre’, meaning ‘hill’, and the Anglo-Saxon ‘hyll’. Thus, the name once meant ‘hill hill’. This kind of synthesis is evidence of two peoples assimilating – absorption, not conquest – and it is the kind of linguistic detective work that Tolkien found compelling, revealing the lost history of a people in the roots of words.

Bree is just over the border from Oxfordshire, and Tolkien spent most of his professional life in Oxford, joining the university in 1925. Given that his academic output dried up almost entirely after 1940, it would hardly be surprising if some of his colleagues felt ambivalence towards him – particularly since many in the faculty believed pre-Conquest languages unworthy of study.

That might be one reason why Tolkien identified the Radcliffe Camera – the 18th-century domed Palladian library that is now part of the Bodleian Library – as the model for Sauron’s temple to Morgoth, the first of Middle Earth’s dark lords, in The Silmarillion.

Barrows and a white horse

Tolkien’s beloved mother came from the West Midlands and he came to regard that inheritance as central to his identity: he once told his son Christopher that he thought of himself as Mercian (from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom that now comprises the Midlands).

This affinity finds its clearest expression in Middle Earth in the heroic people of Rohan. Their very name for their land, The Mark, is how the Mercians might have identified themselves.

And the symbol of Rohan, the white horse in a green field, can still be found defiantly cut into the hillside at Uffington, on the Berkshire Downs, marking the borders of Mercia and Wessex.

It is an extraordinary site to visit, since

, scoured into the white chalk beneath the grass, cannot be wholly seen up close: you have to view it from a distance, as the enemies of Mercia might have seen it; bold, austere and intimidating.

About a mile west of the white horse, along the Ridgeway, the last remaining stretch of a prehistoric path that once crossed southern England from the Dorset coast to the Wash, is Wayland’s Smithy, perhaps the best surviving example of a pre-Celtic burial mound in Britain. The site lies in a wide circle of beech trees – a relatively recent creation – its entrance guarded by four fearsome sandstone boulders.

Tolkien’s response to barrows and burial mounds was deeply ambivalent. Perhaps the best known example is Frodo’s encounter with an evil wight on the Barrow Downs. And there is no question that some barrows – Wayland’s Smithy among them – can be chill and eerie places, empty of their dead and echoing with the loss.

But Tolkien also understood the emotional pull of barrows, too; these green graves of nameless and forgotten dead tenderly folded into the contours of our green hills and fields. When Arwen, Aragorn’s elf queen, is lain to rest at last on Cerin Amroth, Tolkien steps back and allows us to see what time does to us, as her name fades from memory and her fame erodes to nothing, leaving just the mound itself, the sole remaining mark of her life.

Drink with Tolkien

Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem in Nottingham is England’s oldest pub. Dating from the 12th century, it is carved out of solid rock beneath Nottingham Castle. It may have been Tolkien’s favourite. “I went to Nottingham once for a conference,” he told to a journalist. “We went to the Trip to Jerusalem and let the conference get on with itself.”

Oxford Tolkien drank at quite a few pubs in Oxford – among them The King’s Arms, The Mitre and the White Horse – but his preferred place for a tipple was the Eagle and Child. He drank here regularly with CS Lewis and the other members of the Inklings – a group of like-minded academics and writers – in the 1930s and 40s.

Mathew Lyons is the author of There and Back Again: In the Footsteps of JRR Tolkien (Cadogan Guides).