Chobham Common luxuriates in the honour of being the largest national nature reserve in south-east England. But its 574 hectares are a fragment of the vast lowland heaths that once dominated this landscape from East Anglia, through Surrey into West Sussex, Hampshire and Dorset.

Seen as agriculturally useless, about 90% of England’s heathlands were destroyed between 1750 and 1980 – ploughed, ‘improved’ by artificial fertilisers, or planted with conifers. The remnants are precious but still fragile, as shown by the murderous slice of the M3 that rudely bisects the site, and the constant threat of urban encroachment.

Today, the flagship reserve of Chobham Common is managed by Surrey Wildlife Trust. Conservation work may appear stark as scrub is cleared and trees felled, but this large-scale intervention is necessary to keep Chobham one of the finest remaining lowland heaths in the world.

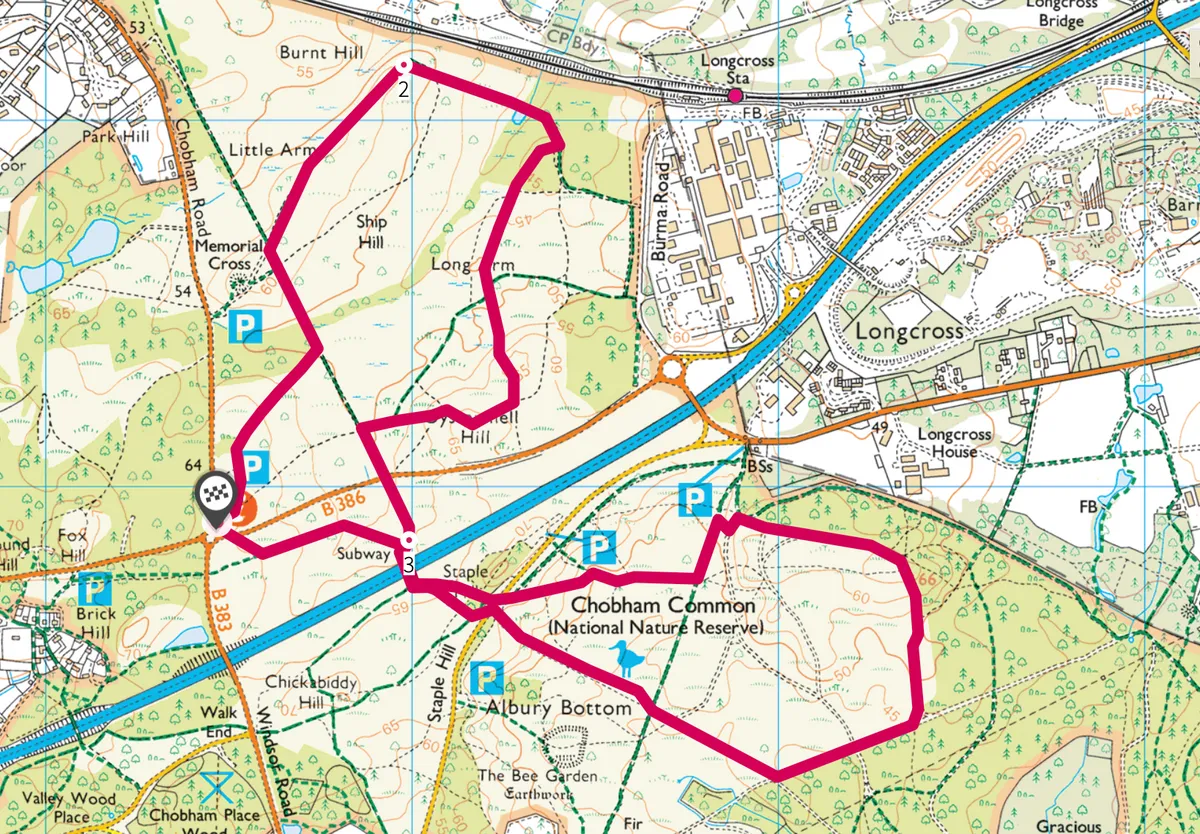

Chobham Common walk

5 miles | 3 hours | easy-moderate

1. Trio of heathers

Start at Roundabout car park on Chobham Road (B383). Take the path north-east through the heather and past a monument. Erected in 1901, the stone marks the spot where Queen Victoria reviewed the troops in 1853 before they departed for Crimea. Even this close to the road, tread lightly and watch your shadow and you may see adders sunning themselves on piles of dead leaves or in patches of bare sand.

There are three species of heather at Chobham: common heather, or ling, with its straggling stalks growing into dense mats and cushions; cross-leaved heath, its stems studded with quadrifoil (four-leaved) whirls; and bell heather, with its softer feathery foliage.

Sand lizard

Larger (up to 20 cm) and stockier than the common lizard, usually with brighter marbling pattern on its flanks. In May, males attain a rich almost metallic green mating display colour. Mostly coastal in England, apart from the inland lowland heaths of Surrey, Hampshire and Dorset ©Alamy

2. Carnivorous plants

Down near the railway line, the ground becomes wetter and treacherous quagmires threaten to engulf the boots of walkers who venture away from the paths. But those who take the chance may spot the bizarre glue-haired, red-leaved, insect-trapping sundews that glisten in the morning sun. For many years there have also been clusters of pitcher plants, North American insectivorous plants that appear to have been deliberately put here. Come back in July and try to find the purple trumpets of marsh gentian, now extremely rare in Surrey.

Near Longcross, loop back and strike out along the narrow paths of dry heath. Be on the lookout for Britain’s largest moth, the emperor. Males – with their bright-orange hind wings – fly during the day in search of the larger, all-grey females that sit low in the heather. In high summer, the

fat green caterpillars, spined like animated cacti, are a wonder as they waddle across the well-trodden paths.

3. Hide and seek

Pass under the motorway and head out into Albury Bottom. The sand lizard occurs here right at the very edge of its British range, joined in August by grayling and silver-studded blue butterflies. As you head across Staple Hill and back beneath the motorway, keep an eye out, or maybe two eyes, for nightjars – they rest almost invisible on tree trunks, logs and stumps, camouflaged against the gnarled and knotted wood. You may have more luck if you take a late-evening walk, when their eerie whirring song haunts the settling dusk.

Chobham Common map

Chobham Common walking route and map