Cronkley Scar, Falcon Clints, Whiddybank Fell, Cauldron Snout. The names have a hard-edged musicality that perfectly echoes the harsh, compelling beauty of the landscape. The huge national nature reserve of Moor House-Upper Teesdale, more than 7,000 hectares in size, is as bleak as any part of England.

Winter lingers in the high valleys long after it has melted elsewhere. Living is hard, yet the hardiest not only survive, they refuse to move away. Among the toughest are the black grouse. Wrapped up against a sudden snowfall, I have seen as many as 40 blackcocks strutting around the hillsides, watched from dry-stone wall perches by a similar number of drab-looking hens.

The male black grouse is an impressive fellow, and he knows it. He displays his iridescent black plumage – enhanced by a forked tail, white rump and red eyebrows – to attract females and deter rivals during the springtime lek.

In decline throughout the British Isles, this large game bird hangs on in parts of Scotland, Wales and the North Pennines, though its reluctance to move beyond its territory means that the small, local populations remain isolated from each other. The Upper Teesdale flock tends to concentrate in the fields around Langdon Beck.

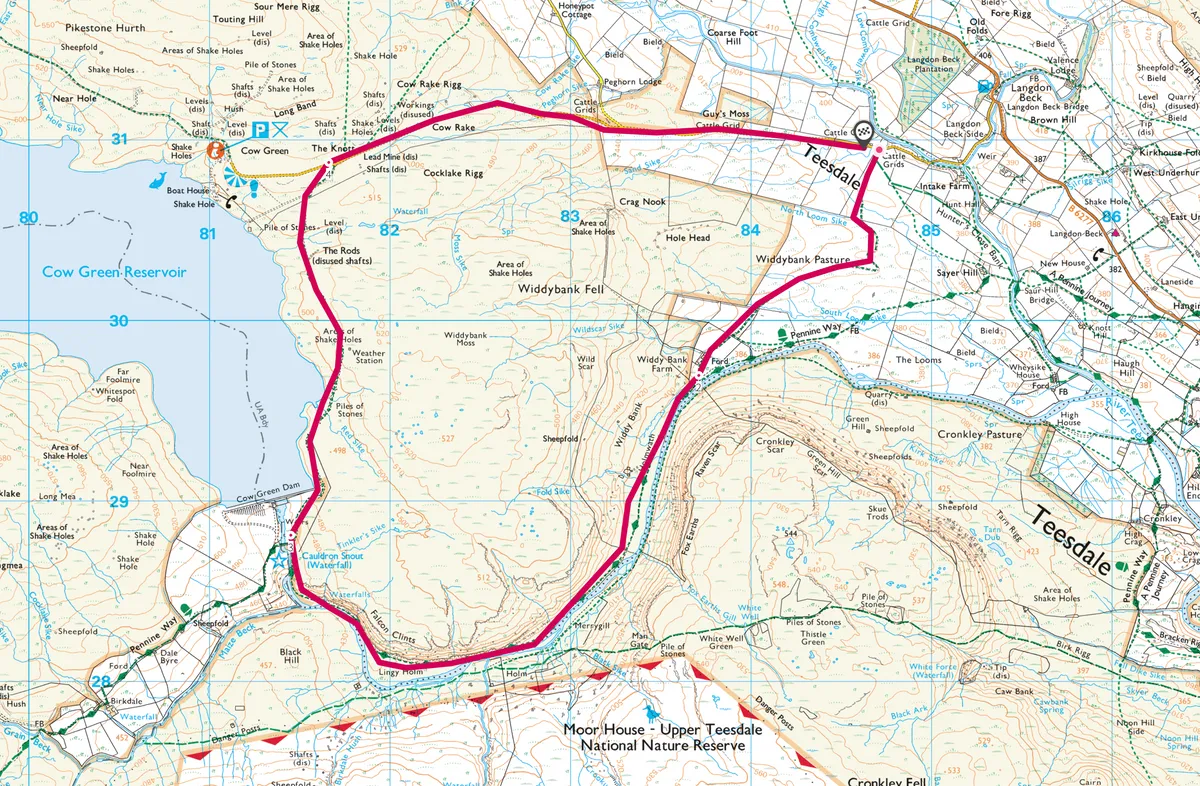

Langdon Beck walk

7.5 miles | 4 hours | moderate

1. Bridge the Beck

Approximately half-a-mile along the road west from Langdon Beck Hotel, a gate opens into the national nature reserve. A good, rough track runs for a mile to Widdybank Farm and a junction with the Pennine Way. If you are content with a short walk, turn east along the national trail for about a mile. Negotiate several styles to a bridge over Harwood Beck, then follow a swampy and indistinct bridleway back to the start (2.5-mile loop walk).

2. The curlews’ cry

Alternatively, carry on along the Pennine Way, following the north bank of the River Tees through a narrowing gorge between Widdybank Fell and Cronkley Scar. The track is level – grassy in some parts and rocky in others, with stretches of wooden boardwalk and large stone slabs.

Across the river is a substantial juniper forest. Along this part of the walk you may be startled at the sudden cackle of a red grouse or the whirring wing beat of a snipe. Watch out for dippers bobbing on the mid-stream boulders or diving headlong into the river.

Many of the waders that nest here – lapwing, redshank and golden plover – will be wintering on the coast, but you can still see the odd individual that has stayed. Even with patches of snow clinging to the hillsides, the piping call of an oystercatcher or the fluting trill of a curlew can evoke a sense of spring.

At this point in the walk the geology of the area becomes prominent. The crags are composed of Whin Sill dolerite, a volcanic intrusion that broke through the older limestone 295 million years ago. As the dolerite cooled and cracked, it formed a large reef of columnar structures, now known as Falcon Clints.

Make your way beneath the impressive bluff to reach the base of Cauldron Snout – at 180m, it is the longest cascade in England. In bad conditions, the River Tees swells in size and you may wish to return the way you have come (six miles).

3. Sugar stone

If continuing, scramble up the side of the cascade (also part of the Pennine Way) to reach the Cow Green Reservoir wall. A good roadway runs north for 1.5 miles to Cow Green car park, passing limestone pavements and small patches where the rock was cooked by the emerging Whin Sill magma into a soft, crumbly form of marble, known as sugar limestone.

4. Remote lodging

From Cow Green, a surfaced road leads east for three miles back to Langdon Beck. The village hotel – which lies “in the middle of nowhere but an hour from everywhere” – offers beds and local food and drink.

Langdon Beck map

Langdon Beck walking route and map

Main image ©Alamy