Deep in Eryri (Snowdonia) lies a lake across which an island once floated. In folklore, this is not unusual. St Brendan’s Isles drifted around the globe for centuries, and seven of Britain’s canonised saints apparently floated to our shores on a sod.

But in this case, the island was real, and unusual enough for Edmund Halley the astronomer to swim out and see for himself in 1698. He described a piece of turf broken loose from the bank and buoyed up by the lightness of “broad-spreading fungous roots on its sides”.

Others will tell you it was the tylwyth teg – the fairy folk – who created the floating island on Llyn y Dywarchen. Respect must be paid to the mischievous tylwyth teg. Their world is a shifting one. They thwarted me with bogs, felled trees, redirected paths, vanishing buses, and even conspired to send me to the wrong lake. There is, it transpires, more than one Llyn y Dywarchen.

Spellbound

Storyteller Gwyn Edwards set me right and, on the banks of the Llyn, leant on his stick and told me the tale of a herdsman who lived long ago on a farm, demolished in the 1970s to make the lakeside carpark.

“He was watching his stock in Cwm Marchnad when he met an especially beautiful maiden with blonde ringlety hair, and eyes as blue as the clear blue sky,” said Gwyn. She was one of the tylwyth teg who lived at Llwyn-y-Forwyn on the lake shore. One night, when the full moon had set behind Y Garn, her father agreed to their marriage on condition that the herdsman never, ever touch his daughter with iron.

“Well it was not a difficult condition to keep,” said Gwyn. “They were happy for many years. They had children, whose descendants still live in Cwm Pennant. The farm was prosperous.” Gwyn paused. The lake shimmered. But one fateful day, the fairy’s horse sank in the marsh at Llyn-y-Gader. Her husband waded in to rescue her, and returned to free the horse but the creature was so exhausted he helped his wife mount his own horse. “Well, that was his mistake,” said Gwyn sadly. “He slid her foot into the iron stirrup,” whereupon the horse, bewitched, plodded back to the lake along the old bridleway with the tylwyth teg dancing in procession. On reaching Llwyn-y-Forwyn, the wife dismounted and disappeared into the fairy kingdom.

“Normally that would be the end of the story,” said Gwyn. “But in this case, the fairy’s mother created a magic island out of turf on which her daughter could stand to converse with her mortal husband on the shore. Time passed, the wife remained young and beautiful, and the farmer grew old. After his death, she was never seen again.” A small brown trout flipped in the water. “And every word of this tale is true,” said Gwyn. And then he vanished.

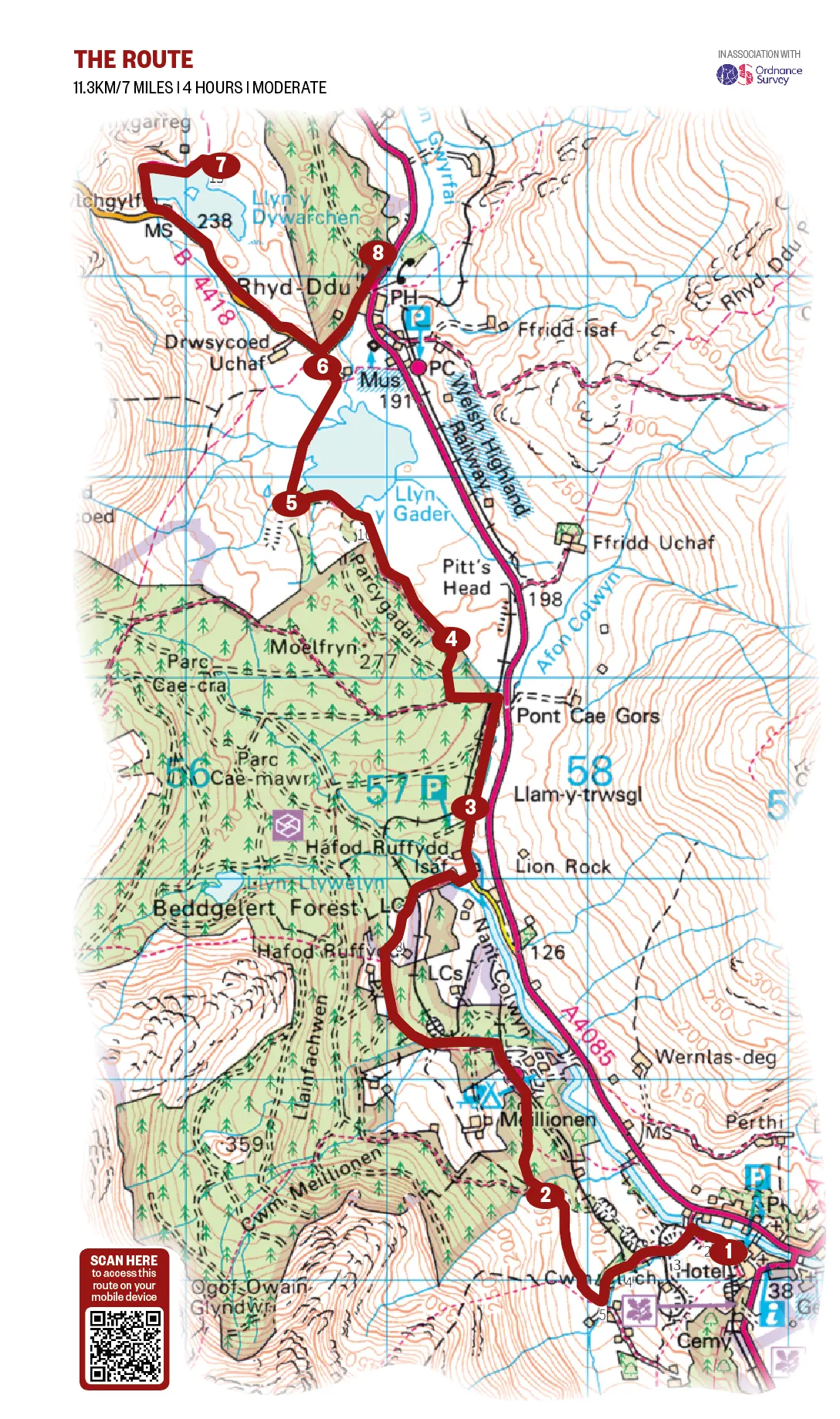

Llyn y Dywarchen walk

7 miles/11.3km | 4 hours | moderate

1. Beneath mounts

To reach Llyn y Dywarchen, begin at the narrow-gauge railway station in Beddgelert and follow the waymarked Lon Gwyrfai route across the track, gradually ascending from Cwm Glo over open farmland. Craggy Moel Hebog towers above you. Look back for spectacular views of Moel-y-Dyniewyd.

2. River and rail

Head into the Beddgelert Forest. Pass the forest campsite, bear right at Hafod-Ruffydd-Uchaf, pass Hafod-Ruffydd-Ganol and cross the railway to reach an 18th-century stone bridge used by horse-drawn coaches. Turn left passing Hafod-Ruffydd-Isaf, and continue, sometimes glimpsing the Afon Colwyn as it dashes over boulders beneath beech and oaks. Pass a car park for forest trails.

3. Sylvan delight

Follow the Welsh Highland Railway track for a short while, then cross it again and bear west into the forest. Dense spruce, intertwined with rowan and holly, are pierced by thin light. Trunks drip. Water trickles in ditches. Larch thins to birch.

4. Wintery waters

The path bears north-west. At Llyn-y-Gader, Arctic char swim and whooper swans and pochards overwinter. Pines are rooted in moss. Snowdon and Yr Aran rise in the east, and Mynydd Mawr and Mynydd Drws-y-Coed soar overhead. At the footbridge, where the horse got stuck in the marsh, look up Cwm Marchnad where the couple fell in love.

5. Slate quarries

Pass the ruined buildings of Cadair Wyllt Quarry, from where slate waste was dumped into the lake, and take the route the horse took across the causeway. Rowan trees grow on rocky outcrops. Cobwebs shine like jewels on the rushes. Floating water plantain weaves through weedy tributaries.

6. Life at the Lake

At the gate, turn left on to the road and head uphill into the Nantlle Valley, where crags encroach and the sky dissolves on dominant Y Garn. Eventually you’ll reach Llyn y Dywarchen, stocked with rainbow trout. Ravens croak above you from Clogwynygarreg.

7. Island afloat

Take the path across the dam wall to Llwyn-y-Forwyn, home to the tylwyth teg. Bog-mosses, asphodel, grasses and rushes grow in the mire. The silver lake ripples with wind. The island you see is of rock, and not the floating island that gave the lake its name; ‘tywarchen’ means turf, first referenced in 1188 by Giraldus Cambrensis. He wrote “it was often driven from one side to the other by the force of the winds; and the shepherds behold with astonishment their cattle, whilst feeding, carried to the distant parts of the lake.” Other writers, too, bore witness; William Camden in 1577, John Speed in 1602 and Thomas Pennant in 1784.

In 1814, William Bingley wrote “there is a small willow tree growing upon it and it is carried to and fro by the action of the wind and water.” But in 1888, a dam built to supply the Drws-y-Coed copper mine diverted the outflow, raised the water level and the island, presumably, sank.

8. A word of warning

Return towards Llyn y Gader and take the road downhill to Rhyd-Ddu where the Cwellyn Arms is usually open (check ahead). From here you can take a bus, or, depending on the season, a steam train, back to Beddgelert. But do plan carefully, for in my experience, the world of online timetables is a shifting one.

Llyn y Dywarchen Map

Llyn y Dywarchen walking route and map