The 11 Clwydians – a run of modest hills that you sink between and then promptly crest, with the breeze raking your hair and the sky scrubbing the heather – stretch south from Prestatyn for 20 miles between the Dee Estuary and Vale of Clwyd.

Despite their location close to the Welsh border, the hills – as with all our landscapes – show evidence on their shapely summits of tensions between man and nature rather than the English and Welsh. By the time the Deceangli tribes built their fortified camps in the Iron Age, these hills already had a story to tell.

Our guide looks at the Clwydian Range in Wales, including history, wildlife, the Clwydian Way and walking route.

History of the Clwydian Range

This story is revealed by the pollen in peat cores analysed by Fiona R Grant in 2009. After the glaciers’ retreat, an open wooded canopy of birch, pine, willow and juniper graced the tops, while oak, elm, alder, lime and ash mantled the slopes. Before long, Mesolithic hunter-gatherers began burning the woodland to attract grazing herbivores. The denuded summits then became dominated by alder carr, open water, marginal fen and damp grassland of sedges, meadowsweet, buttercups, parsleys and pinks.

Having introduced agriculture to Britain, Neolithic people gradually continued the deforestation, grazing animals in the uplands and cultivating cereal. This practice continued to a greater extent in the Bronze Age, when the climate was balmy, and even when it wasn’t, in the Iron Age, during which time the Deceangli built their forts. Cereal pollen from this time suggests that some fertility, due to glacial clays and underlying limestone, had been maintained, even while similarly degenerated uplands elsewhere in Wales had already become heather moorland, which thrives on eroded, impoverished soils. Occasionally, respite was granted with human retreat following the Black Death and Glyndŵr’s rebellion, allowing woodland to grow back, but by now the pattern was set.

Whatever you think of the current management plan that actively maintains heather moorland and the specific wildlife it sustains, the hills are a rippling riot of colour in both spring and summer, granting breathtaking views you wouldn’t see if woodland were allowed to return. Yet still, even now it is trying to, as seen in the small birch and rowan saplings rising from the heather.

The Clwydian Way

Navigating the hills and surrounding valleys, the Clwydian Way, a 122-mile circular route, takes in the towns of Prestatyn, Llangollen and Corwen, and explores Loggerheads Country Park, which has mixed ash woodland and limestone grassland, Llyn Brenig (a reservoir), and Coed Clocaenog, where red squirrels thrive. clwydianway.co.uk

Birds of the Clwydian Range

Black Grouse

In the spring lek, ‘blackcocks’ – violet-black males with white wing-bars and red wattles – strut, leap and lift lyre-shaped tails, revealing white under-feathers in the hope of attracting a ‘greyhen’.

Red Grouse

Also sustained by heather moorland, red grouse spring from the heather when startled, with a fruity chuckle and whirring wings, leaving you with an impression of rufous plumage and red wattle.

Ravens

The largest members of the corvid family, ravens can be seen somersaulting in warm air currents off the edge of Foel Fenlli, grunting, cronking, tumbling and even flying upside down.

Clwydian Range walk

17.5 miles | 9 hours | challenging

1. Rising ways

This challenging walk (take two days if you prefer) forms a section of the Offa’s Dyke Path and is generally well signed. From Bodfari Church, pass the Dinorben Arms and turn left on the A541. After 200m, join the Offa’s Dyke Path to the right, crossing the Afon Chwiler to climb hedged lanes into sheep fields.

2. Great forts

At the path junction, head through a gate marked Cilffordd Byway, then bear left (south-east) uphill, high enough now for fabulous views of the Vale of Clwyd as the path climbs through bracken heath to heather.

At 20 hectares, Penycloddiau is the largest of six Iron Age forts built on these hills, and one of the biggest in Wales, with multiple concentric ditches. The ramparts would have been timber-breasted and the interior crowded with ponds and thatched roundhouses.

3. Green woods

Notice the increase in birdsong as you skirt the edge of Coed Llangwyfan, a recovering mixed Natural Resources Wales (NRW) woodland with birch, pines and a scrub understorey that shelters ferns and mosses. Descend to the car park and woodland trails.

The track belts rather than crowns Moel Arthur, where a much smaller Iron Age fort was powerfully enclosed with comparatively large banks and ditches. Descend to a road, then climb Moel Llys-y-Coed, looking out for buzzards, kestrels, wheatears and meadow pipits.

4. Valley lodgings

If you’re heading for accommodation at the Golden Lion in Llangynhafal, follow the waymark pointing into the Vale of Clwyd to your right.

Otherwise, continue over Moel Dywyll. The strips in the hills ahead are where the heather has been razed to provide lekking places for black grouse.

5. Mother hill

There is usually a party atmosphere on 554m-high Moel Famau, the mother hill. Jubilee Tower, the incomplete, Egyptian-style monument, was built in 1810 to celebrate George III’s jubilee.

Descend on a Bronze Age track. Bwlch Penbarras is a good place to admire the Vale of Clwyd and its scatter of medieval towns. Cake and coffee are available in The Hut, a shepherd’s hut café, open in season. Just half a mile down the road, Coed Moel Famau’s many paths include an Arboretum Trail, featuring all of Britain’s native trees.

6. Rich pasture

Leave the crowds for Foel Fenlli. The ‘improved’ sheep pasture and post-and-wire fences of Moel Eithinen are a startling bare contrast to the heather moorland, especially if you’ve been comparing the latter to woodland. Drop into flat fields along a line of oaks, and round the foot of similarly nitrogen-enriched Gyrn, through a

larch copse.

7. Returning trees

Join the A494 briefly at Clwyd Gate, before climbing again. Nature is being allowed to reclaim Moel Gyw, where birch, pines and rowan sprout from shrubby heather and gorse, again with a noticeable increase in birdsong and activity. Continue on a sinuous contour around Moel Llanfair, with views over shadowy vales.

8. Down to the Alyn

Meet the road to Llanarmon-yn-Ial, then ascend on to the improved pasture of Moel y Plas and Moel y Gelli. Pass a radio tower and Llyn Gweryd fishing lake to join a lane.

Cross the stile and descend steadily through sheep fields, stile after stile, until the land levels between quiet hedges.

Water voles apparently live in the River Alyn, which rises in the Clwydians. Here it meanders over a sandy bed under dusky green trees across a waterlogged plain.

9. Old drovers’ village

When Llandegla was a drovers’ village, it was served by 16 inns, a livestock market and a smithy. Scant on pubs now, the village offers a welcoming Community Shop and Café and medieval St Tecla’s Church, named for a first-century Central Asian saint whose well lies a short walk away.

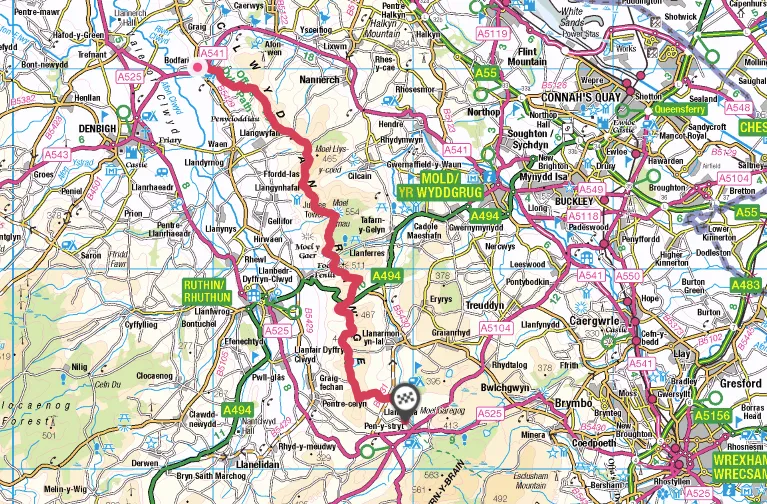

Map

Clwydian Range walking route and map