If you want to witness a bunfight, come to the sedate Georgian city of Bath, in Somerset. The humble Bath bun, which has graced the lace table-clothed tearooms of the city for more than 300 years, has provoked more than its fair share of controversy.

So why all the fuss? Well, the problem with the bun’s story is that it is actually a tale of two buns. The first is a domed, bread-like creation that was brought to this country by a young French refugee, while the second is a mass-produced stodgy cake that calls itself a Bath bun, but that purists say is nothing of the sort.

History of the Bath bun

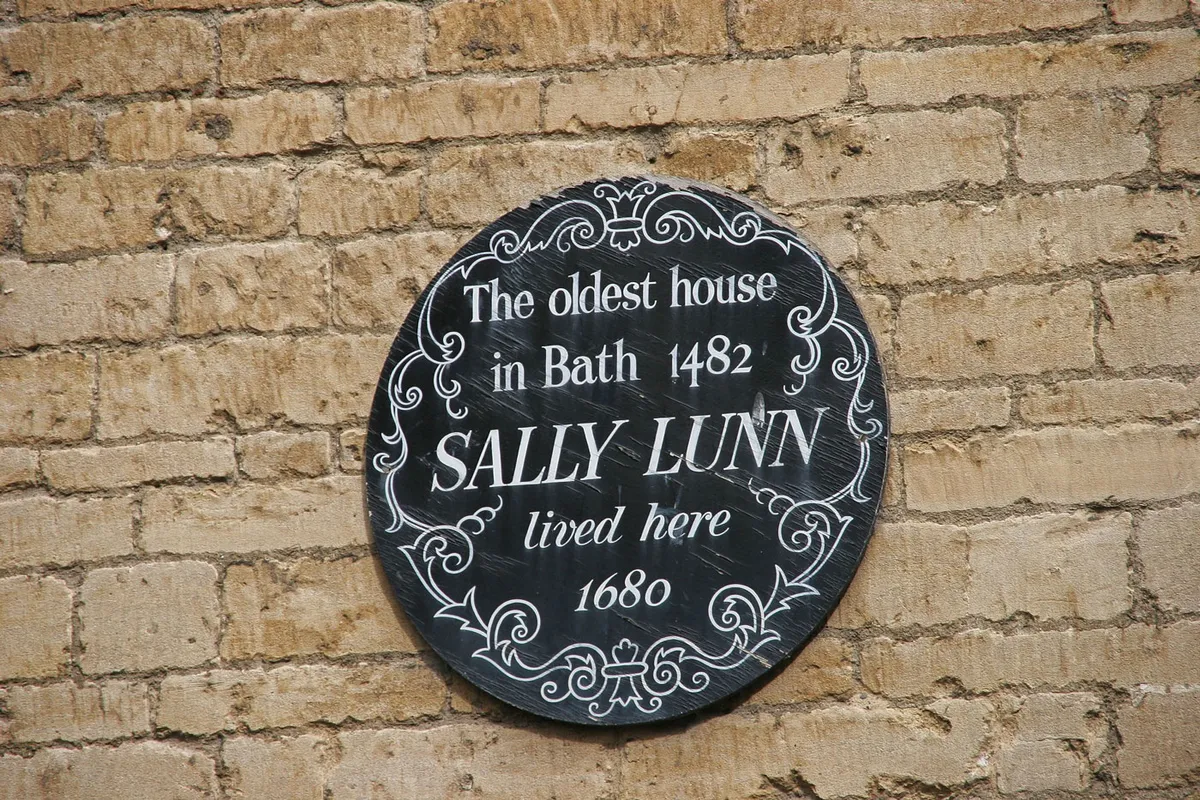

The original bun, according to some food historians, was first baked in Bath by a Huguenot refugee called Solange Luyon, who fled to the city in 1680 after escaping persecution in France. Solange, or Sally Lunn as she became nicknamed by locals, found work with a baker and introduced him to a bun that she used to make at home. It was a generous-sized brioche, more like a French festival bread than what we now call a bun.

The fame of Sally Lunn’s airily light bun grew alongside that of the magnificent city she’d made her home. Some even called the bun the Sally Lunn, among them Charles Dickens, who mentioned Sally Lunn in his book The Chimes. Novelist William Makepeace Thackeray endowed the bun with a hint of spice when, in Pendennis, he described a “meal of green tea, scandal, hot Sally Lunn's, and a little novel reading.” Jane Austen, however, was less enthusiastic on the one occasion she mentioned them, complaining in a letter in 1801 of “disordering her stomach with Bath buns.”

A bun for every meal

Served with sweet or savoury accompaniments, the bun was effectively used as a plate or ‘trencher’ for meals that were placed on top of it. At Sally Lunn’s tearoom, located in the tall medieval building where Sally baked her original buns, the buns are still eaten in the same way – savoury, with toppings such as Welsh rarebit; sweet, coated with homemade lemon curd or cinnamon sugar; or as the backdrop to a meat dish, such as Beef bourguignon. Always toasted.

“The joy of the bun is its versatility,” says owner Jon Overton as he hands me a slice of the tearoom’s best-selling Welsh rarebit bun, topped with local bacon. “It has a wonderful way of absorbing and enhancing the taste of whatever is served with it. Like a croissant, it is great with sweet or savoury. Occasionally people come in and say it’s just a burger bun and a rip-off. They don’t get it.”

Like most foods, the bun evolved. With time, people outside Bath wanted to enjoy the bun so tried to recreate it, adapting the recipe to suit modern tastes. The biggest change came in 1851, when the Great Exhibition spawned the mass-produced machine-made London Bath bun. Records show that a phenomenal 943,691 Bath buns were consumed over the five-and-a-half months that the exhibition lasted.

Today, if you treat yourself to afternoon tea at the Pump Room in Bath’s ancient Roman Baths you’ll be served a small, sweet bun with sugar nibs and currants on top – quite different from the Sally Lunn version, but a Bath bun all the same.

This sweet bun, however, has failed to satisfy purists, who dismiss it as small, stodgy and sickly. Elizabeth David, who wrote the definitive English Bread and Yeast Cookery in 1977, was adamant that the London Bath bun should be distinguished from the Bath bun of Bath. The Sally Lunn bun, she wrote, “differed greatly from a version downgraded by bakers into the amorphous, artificially coloured, synthetically flavoured and over-sugared confections we know today.”

Jon Overton is in no doubt that he is the guardian of the original Bath bun. When his father, a baker himself, bought Sally Lunn’s tearoom in the 1980s, he inherited Sally’s original recipe with the deeds. The recipe had been rediscovered in the 1930s in a secret cupboard over one of the many fireplaces in the basement kitchen where Sally had worked. Jon’s father handed the recipe to the tearoom’s bakers who, sworn to secrecy, started producing the buns once again.

“Today, only six people know the recipe: three bakers, me, my business partner Julian Abraham, and my dad,” says Jon. “The document itself is locked away in a solicitor’s vault. We keep the recipe in our heads.”

Jon has just heard that a Bath bun shop has opened along the street and is selling cakes that it is calling Bath buns. He’s not amused. “These are no relation to the true Bath bun. Sadly they cause confusion.”

Tourist attraction

On the table next to ours, a couple are clearly blissfully unaware that they are munching into a minefield. They’re only in Bath for two days but are already on their second visit. “We couldn’t keep away,” says Phil Bagge, from Southampton, tucking into a lemon curd bun priced at a very precise £3.48 (one of Jon’s dad’s eccentricities was to end all prices with an eight). Some Bath residents are equally enthusiastic. “We have one lady called Jean who comes in every day to eat a bun,” says Jon. “She always arrives five minutes before opening time to be sure of a table.”

All attempts to get the recipe out of Jon, however, are in vain. Does the bun contain butter and eggs, like a typical brioche, I venture. He’s not saying. Its ingredients will, it seems, remain a tightly kept secret for a few more centuries to come. Meanwhile, the battle of the buns rages on.

Sally Lunn’s, 4 North Parade Passage, Bath 01225 461634