Extreme stormy weather and flooding has caused widespread damage to many towns and homes across the UK.

Our guide to flooding in the UK looks at the environmental impact and considers whether climate change is to blame and whether it is possible to prevent.

What happened?

Updated: 18th February 2020

More than 270 flood warnings and alerts, including eight severe flood warnings are in place across England, Scotland and Wales and Scotland, including nine severe - or "danger to life" - warnings for the rivers Lugg, Severn, Wye and Trent. Up to six people are now thought to have died.

In Hereford, the River Wye reached record levels, with a water height of more than 6m recorded at Hereford Bridge and levels the highest in the river’s 200-year recorded history. South Wales valleys recorded their highest river levels for more than 40 years.

The Severn has also caused concern with residents of Upton-on-Severn advised to evacuate their homes after high water breached flood defences.

The intense rainfall has been the most significant feature of Storm Dennis, which pummelled much of the UK over the weekend. The storm followed swiftly after Storm Ciara, which hit the UK over the weekend of 7-9 February and caused at least three fatalities. Ciara triggered 186 flood alerts and left 530,000 people without power. The strongest gust, of 97mph, was recorded at the Needles on the Isle of Wight. Flooding from Storm Dennis has been exacerbated because many flood plains and soils are now saturated, both by Storm Ciara and previous heavy rain.

The back to back storms follow last autumn’s floods, when a months’ worth of rain fell in only a few hours in early November in parts of the Midlands and Yorkshire as reported in February’s issue of C. According to the Centre for Hydrology and Ecology (CEH), summer and autumn 2019 were exceptionally wet in northern, central and eastern England.

More heavy rain is forecast for the end of this week and in the last week of February. The government has said there is no need for Cobra, the emergency committee, to meet; during the floods before the election in 2019, a Cobra meeting was held. A government spokesman said the Prime Minister Boris Johnson was receiving regular updates. Opposition spokespersons have criticised his decision not to visit affected areas.

Climate modelling by the Met Office suggests that although climate change may not bring more storms to the UK, those that do arrive are likely to be more intense, with stronger winds and more rainfall falling in shorter periods.

Looking back on 2019

A month’s worth of rain fell in only a few hours in early November in parts of the Midlands and Yorkshire. Sheffield saw 84mm of rain in 36 hours and one woman was killed. Almost 50 flood warnings were issued, including several ‘threat to life’ alerts across Yorkshire. Hundreds of homes were flooded in the village of Fishlake (pictured), which was cut off by water from the River Don. In Wainfleet in Lincolnshire, two months’ worth of rain fell in just two days.

Big floods in Yorkshire

In 2007 River Don overtopped it banks, causing widespread flooding in Sheffield. More than 35,000 people were affected by flooding in Hull, with 700 people affected in Doncaster; much of Barnsley and Rotherham were also cut off.

In 2015 the rivers Foss and Ouse meet in York. On Boxing Day, 600 properties were flooded. More than 4,000 properties

were affected in Leeds by the River Aire.

Was the heavy rainfall a one-off?

No. According to the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH), summer and autumn 2019 were exceptionally wet in northern, central and eastern England. In the summer, localised but severe flooding occurred in Lincolnshire, the Peak District and Yorkshire Dales. In October, the jet stream tracked south, propelling cyclonic systems across the UK. With soils already saturated, rainfall on 7 November prompted the highest-ever peak flows for catchments in South Yorkshire, Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire.

We need a national conversation about trade-offs and a bit of realism. There are limits to what protection you can achieve when you get really prolonged and heavy rain. Unfortunately, some places will get protected, others won’t. Climate change makes it possible that significantly more houses are going to be at risk.

Professor David Demeritt

Is climate change to blame for flooding?

The science is straightforward: a warmer atmosphere holds more moisture. For every 1ºC increase in temperature, the air can hold about 7% extra water vapour. Winters are becoming warmer and wetter, so the ground is often saturated and unable to absorb sudden bursts of extreme rain. “There has been an increasing trend in flooding over the last four or five decades in parts of northern Britain and this is at least consistent with what we may expect in a warming world,” says the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology.

What is climate change and how does it affect the UK?

Extremes of weather, flooding and coastal erosion have all affected the UK countryside in recent years. Our guide explains what climate change is and how it affects British food production, wildlife and the countryside, plus how you can help.

What’s the solution?

In 2016, we spoke to author of Taming the Flood. Rivers, Wetlands and the Centuries-old Battle against Flooding, Jeremy Purseg's love about whether climate change is to blame and what the next steps need to be.

Read the interview with Jeremy Purseg

Once ever 100 years?

The likelihood of a flood event occurring is usually expressed in terms of its predicted frequency of return. For example, a flood may be referred to as a 1-in-100-year event or as having a 1% probability of being equalled or exceeded in any one year.

It can sound counter-intuitive but low-probability floods, considered over a long period of time, have a significant likelihood of happening. For example, a 1-in-100-year flood has a 25% chance of occurring at least once in a 30-year period (a typical mortgage duration) and a 50% probability of happening at least once in a 70-year period (a typical human lifetime). The Somerset Levels suffered 1-in-100-year floods in 2012 and again in 2014.

“Just because it happens once, it doesn’t mean you are good for the next 100 years,” says David Demeritt, professor of geography at King’s College London.

How to mitigate the impact of heavy rain and flooding

1

Stop building on floodplains

Sheffield, Doncaster and Rotherham are all built on the River Don’s floodplain. Fishlake is located in the epicentre of the floodplain zone. “Planning has been supposed to steer away from floodplains but it hasn’t worked, partly because local authorities have requirements to build new housing,” says David Demeritt, professor of geography. “We have developed lots of floodplains – first draining them for agriculture and then, often, subdividing for housing.”

2

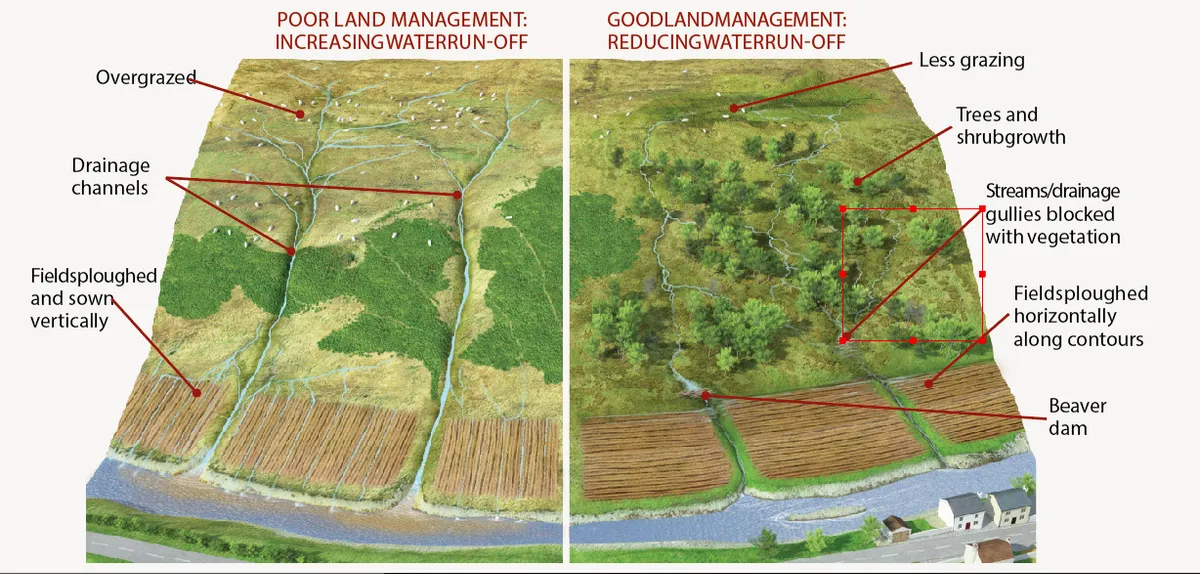

Manage the uplands to hold water back

The way water is managed upriver – before it reaches floodplains – is also key. This applies to upland areas, such as the water catchment areas of the Pennines, and lowland regions, such as around the Thames, according to Martin Evans, professor of geomorphology at Manchester University.

In the Pennines, the Making Space for Water Project has shown how restoring degraded moorland can reduce the volume and speed of water run-off. Measures included blocking gullies and returning vegetation where there was only bare peat. As a result, water tables have risen by 35mm, peak storm discharge is reduced by 35%, and lag times increased by an average of 28 minutes.

“It’s one measure that can help to make flood peaks longer and lower, rather than having flash floods,” says Evans. “If it means the peak flow is 5cm below your doorstep in Doncaster rather than 5cm above, it has made

a huge difference.”

However, Demeritt says such measures have limited impact. “Land management is a good thing for biodiversity. We should be doing it anyway. But it only really works for moderate rainfall. When you get crazy rain falling for weeks, it doesn’t make

much difference.”

3

Allow farmland to flood

Farmers may be paid to allow their land to flood. “It’s easier and cheaper to store water in fields than in your kitchen,” says Demeritt. “It’s an idea that seems worthy of subsidy.”

In lowland areas, livestock grazing can compact soil, raising water run-off. Changes in grazing times and farmers ploughing land along contours can reduce water flow during heavy rain in lowland areas. “That comes at a cost to farmers, so there is a discussion about how you pay farmers for this service,” says Evans.

4

What about dredging?

“There has been an awful lot of garbage, if not factual untruths about dredging,” says Demeritt. “Dredging gives a bit of extra capacity in the drains, so a bit more rainfall will drain away faster. But it won’t make any difference with really heavy rain. If you dredge, the water ends up in someone else’s kitchen downstream, more quickly.”

What is dredging?

Dredging removes silt from the riverbed, allowing rivers to hold more water – and to remove floodwater more quickly.

What are the drawbacks?

The Environment Agency has warned that in order to stop rivers bursting their banks they would need to be dredged several metres wider and deeper.

It has also been claimed that the greater volumes of water carried by dredged rivers could lead to serious flooding in towns downriver.

Conservations have expressed strong concern that dredging destroys delicate wildlife habitats such as fish spawning areas and freshwater mussel beds.

What are the alternatives?

Other suggestions focus turning upland pastures into bogs, effectively soaking up rain like a giant sponge and releasing it more slowly. Extensive tree planting in the catchment area may help to soak up excess water before it reaches low-lying areas. De-canalising the rivers, allowing them to meander, may also slow the force of floodwater.

5

Be responsible

“People have to take some responsibility when they buy,” says Demeritt. “Rather than blame the Environment Agency, they need to look at a floodplain map. It’s nonsense to think it’ll be okay because the area has never flooded before.”