In our village there lived a mystifying alchemist. Known throughout the land for his art and gamesmanship, his creations were mesmerising and baffling. Then, one night, he secretly buried a golden hare and laid a trail that navigated the world to find it.

Although our schooldays came sometime after the wonder of Masquerade, it was the most exciting thing to have happened to our village. Enthusiasm had reached out beyond our borders, across the world, from Texas to Japan. Since then, I’ve got to know Kit Williams and his family at his annual exhibition (he’s painted many people from the village, including me). One spring day, some time ago, I joined him on his daily trail.

“My best ideas come from this walk. Something will occur perhaps on the radio or I’ll read something. On its own it doesn’t have enough to it. But then a day or 15 years later, something else occurs and by marrying the two, something wonderful comes out of it. Look, there’s sorrel, we used to eat it for the vinegar flavour.” It’s the first of many spring flowers that guide us through the woods and Kit’s mind, as we snake through treacherous carpets of garlic. “Careful, you can slide right down the bank and go home with your clothes stinking of the stuff,” he says.

Medieval mystery

“There’s something very special here; I’ve been looking for herb-paris for 30 years. These only came out yesterday. After the woods were coppiced, suddenly they all came up. When I was painting A Midsummer Night’s Dream, a crew wanted to film me picking one but I couldn’t do it, especially on tv, so I made one out of card, bamboo and a bead. We planted it and made it look like I was picking it. One of the girls in the film got married so I gave it to her as a wedding present.” A gift that honours Kit’s interest in our medieval ancestors, whose herbalists recognised its whorl of four egg-shaped leaves as equal and harmonious and who used the plant in marriage rituals.

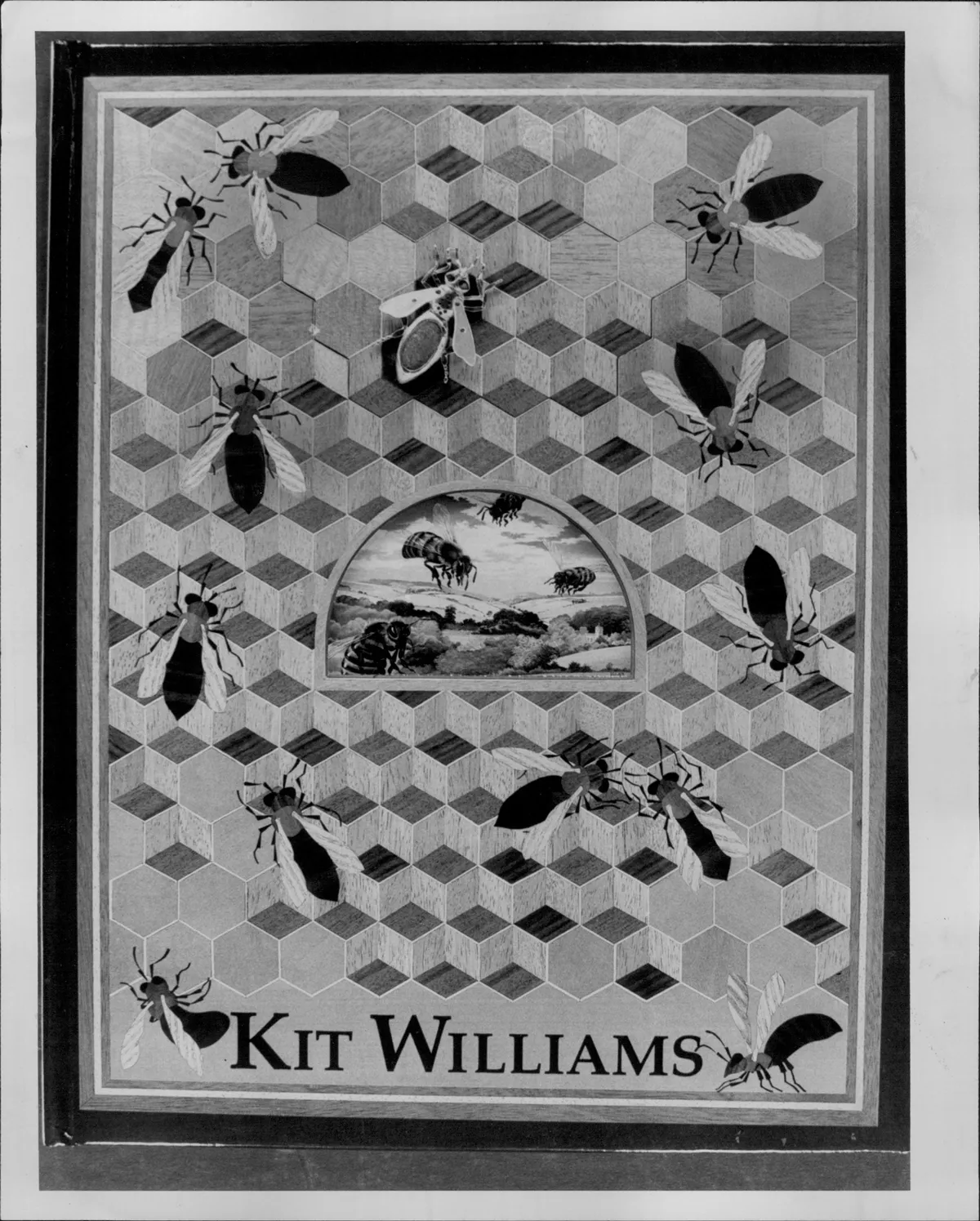

“When I was doing the Masquerade, I got interested in medieval riddles to get people to look hard at the book. Like this one: ‘there were five brothers at the same time born, two were bearded and by two no beards were worn, the fifth, not to cause his brother’s shame, wore one side bearded and one side plain’. It’s the sepals of a rose. Prickles on the trailing edge to stop insects getting in. Any rose, wild or cultivated, you will see it every time. I thought ‘wow, that’s fantastic’; I love that someone observed that little thing.”

“I’m not really interested in puzzles, more physics and maths formulas. I like to know how things work and then want to paint them. I’ve painted a lot of dandelions. They have two sets of sepals: the first set opens up and the second set is closed. Then the second set opens up, the yellow flower comes out, gets pollinated and the second set closes up again. Then seeds push the petals out and these sepals open for a second time. So what function does the first set have?” It’s certainly more attention than I’ve ever given to dandelions. “We just offered them to friends to smell and then used our thumbs to ping them into their faces,” is my clumsy offering.

But it’s this attention to detail that draws us into Kit’s pictures. “In this part of the world we live life in great astronomical buckets where ferns and pennyworts are at eye-level so you see more. I may get a piece of turf, put it on a tea tray and water every day to see what creatures crawl out. Animals are anthropomorphic in my work and when I paint I become like an actor inhabiting each character. I was the hare and all of the characters in the Masquerade”.

As we go, the sun shrinks the shadows a little more today than yesterday, the mysteries that ebbed back into the earth once upon a time, appear now from warmed soil, inciting stories: “On dewy mornings, we’d get a piece of twig and shape it into a hand mirror to collect cobwebs. By the time we got to school it had melded into a rubber glass and as it dried you were left with a filigree of cobwebs.” We used to make brooches out of this, we called it goose grass. “It is goose grass, or sweet hearts… we’d take an ash bud on Ash Wednesday and put it in our lapel…”