In winter-time an island battens down its hatches. Folk have more time for one another: the pace of life is slower. You can’t rush the mending tasks that have to be finished; you have to accept when the hail’s coming down in clouds or there’s a high wind rattling the house. There’s time for talk.

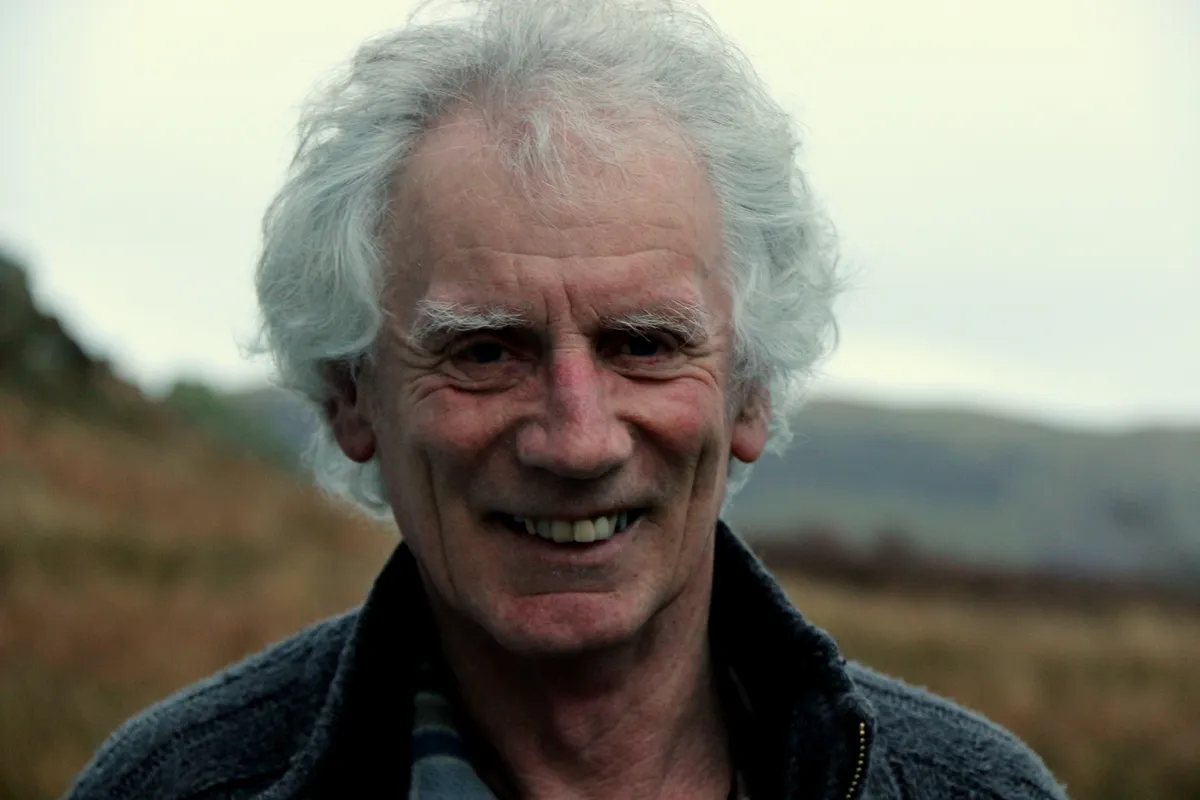

Kristina and I went down to the very south end of our island of Seil to Cuan, to talk to Keith McLean. We know him from church, but there’s only the chance then to nod and smile and ask how things are going. We want the opportunity to speak properly: to have a real blether.

Keith lives almost where he grew up, there where the Cuan Sound separates our Isle of Seil from the neighbouring island of Luing (pronounced ling, like the fish). On a good day you could easily have a conversation with someone on the other side, the stretch of water between the two islands being so narrow. But that’s as far as any thought of swimming goes. It’s the most extraordinary bit of water I’ve ever seen; it gushes from east to west like a river, and a river in spate. The whole channel is a boiling pot of swirls and eddies.

To think that Keith’s grandfather actually rowed passengers across early last century almost beggars belief, but then there were other ferrymen elsewhere who made such crossings in open boats. In those early days it cost thruppence.

Keith smiles, remembering the story of one man who never seemed to have sufficient in his pocket to pay. Keith’s grandfather knew the man of old: on this occasion he rowed him halfway across the Sound and then drily informed him he would now need the second half of the fare if the man wanted to be rowed to the far shore.

Keith grew up with his grandparents: they spoke to him in Gaelic and he answered in English. Gaelic was on the retreat by then: today it’s just found in a few last corners in these Atlantic Islands. Keith has been all manner of things since growing up on Seil: he’s worked for years on the ferry over the Cuan Sound, and even now in retirement does the odd stint. He must know every rock and ripple of the crossing.

But he’s done everything from panning for gold in the Argyll hills to fishing for lobsters, and plenty in between. His life has been spent here and it’s clear he loves this land and seascape, and knows it well and truly.

Inevitably we find ourselves talking about what he’s seen in that channel of water not many yards from his back door, because even now in mid-January it’s busy with birdlife. When we leave the orange glow of the coal fire and the snug of the sitting room to go out to look at one of his boats (he has two: one that leaks more than the other), a cormorant comes gliding over the Sound.

It’s an amazing place to stand: in the half-light we look straight south down the narrow channel of water that runs between Luing and the mainland. Keith tells us of the otter he saw a few yards away in the rough ground next to the house. It’s not all that long since he watched a pair of white-tailed eagles not far down the Sound on the uninhabited islet of Torsa.

In the summers the dolphins come wheeling through the Sound: Keith tells us how four of them joined his boat, two on each side, and then dived under the boat to swap sides as though for nothing more than the sheer fun of it.

Yes, we sit talking dolphins and eagles and otters until the last of the January light is all but done. We come away with something special, with something that money could never buy.