Hidden in the folds of Oxfordshire’s hills like a jewel secreted into a crumpled handkerchief, the village of Ewelme seems like the perfect rural idyll.

A village of wobbly red-brick cottages and haphazard, meandering lanes, it is crowned with a low, broad church built from a chequerboard of flint and stone.

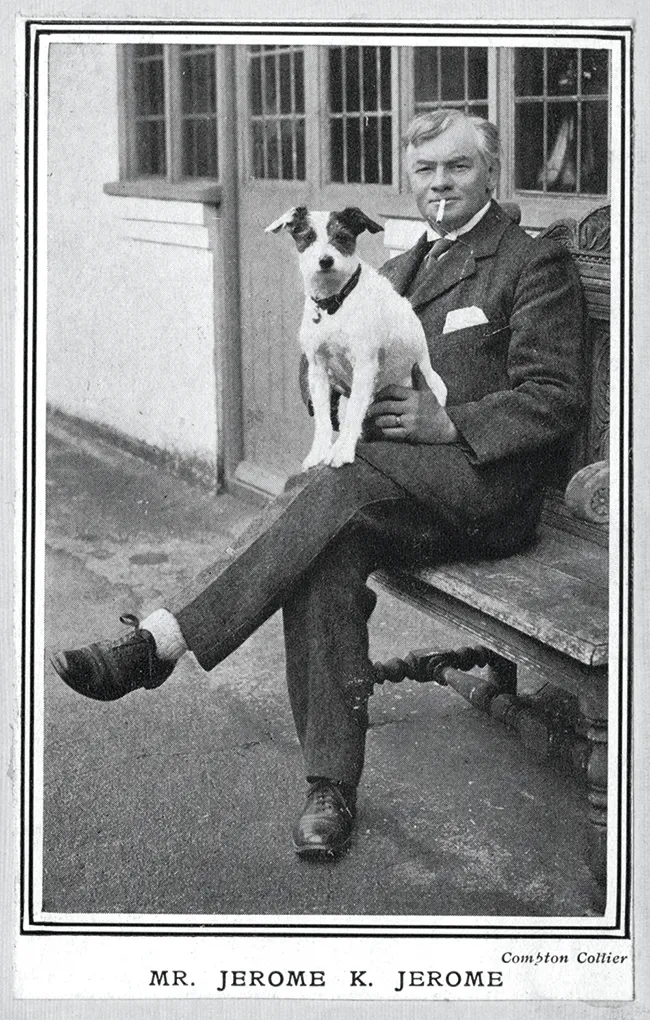

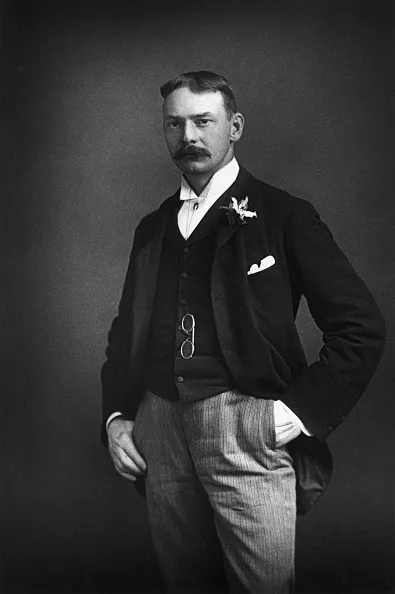

Since 1927, Jerome K Jerome – gifted humorist, wit, author and sometimes editor of the Victorian incarnation of The Idler – has lain in God’s Acre under the distinctly industrial epitaph from Corinthians: “For we are labourers together with God.”

Biblical snubs of the idling lifestyle aside, Jerome’s resting place – having spent the last years of his life in the parish, close to the River Thames celebrated in his most famous work, Three Men in a Boat – is appropriate, for Ewelme is Old English for ‘waters whelming’.

Born on 2 May 1859 in Walsall, Staffordshire, Jerome was the youngest son of a successful preacher and church architect – albeit also a failed farmer, ironmonger and the owner of a flooded colliery who lost his fortune on his son’s first birthday. Like his father, Jerome had wide interests and varied professions. During his working life, he turned his hand to railway clerk, journalist, actor and pauper, but he found particular fame in 1889 as the author of the much-loved humorous travelogue Three Men in a Boat (To Say Nothing of the Dog).

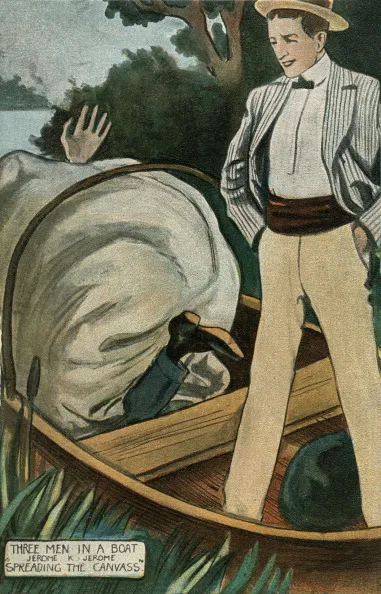

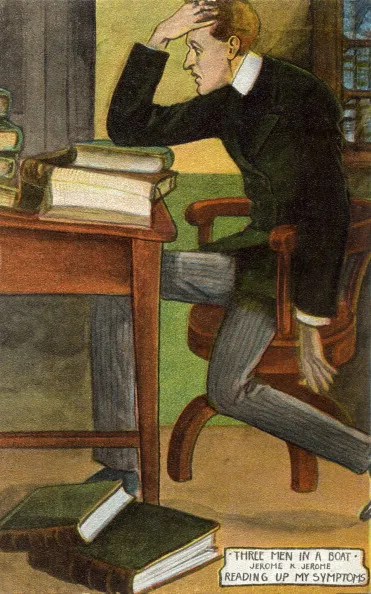

A love of the Thames and a honeymoon spent boating the preceding year had inspired Jerome to write a study of the river. He started by working on the entertaining bits first – the “humorous relief” as he put it – and then framed those with passages of history. His publisher cut most of the serious content and, had he not, it might not have remained in print for long enough to sell millions of copies all over the world.

Jerome’s common touch and his eye for the vernacular ensured that Three Men in a Boat’s reception by the critics was hostile, who derided it as reading for working-class Londoners. “One might have imagined that the British Empire was in danger,” wrote Jerome of the criticism in his autobiography. However, those working “’arrys and ’arriets”, as the literati snobs of the day would have it, made the book an outstanding success. His publisher said he paid Jerome so much in royalties, he wondered what became of all the copies. “I often think,” he told a friend, “that the public must eat them.”

The genius of Three Men in a Boat is that a book about a party of young city clerks messing about on the water in the twilight of their bachelorhoods is not just a story of comic ineptitude, of pratfalls and farce, but a paean to the Thames itself. The river runs right through it. Every chapter is punctuated by vignettes of scenery and history leavened with comical asides and passages that flow around the social mores of the day, while Jerome’s digressions are as liquid as the landscape itself. The novel’s popularity propelled the masses into the countryside to explore the landscape of the Thames valley and the river itself. Boat registrations on the Thames leapt from 8,000 to 12,000 in the year following publication.

If the river has never been quite the same since, neither was Jerome. His book, though successful, cast a long shadow. Jerome spent the rest of his life aspiring to be the next Dickens but feared no critic would ever take him seriously.

What he left behind, when he went for his final lie-down near the river he loved, was a landscape made of words. Sometimes sentimental, often learned and always funny, Three Men in a Boat is a love letter to youthful exuberance and Old Father Thames himself.