It’s comforting to recognise that if you’ve felt it, other people have felt it too. There’s comfort, too, in knowing that as you walk, other people have also walked here. Each step supported the burdens of ancestors before you, it is merely your turn to tread.

This land is well known, every last six-inches-to-the-mile of it. Perhaps better known than any other in the world, thanks to the intriguing history and meticulous mapping of the Ordnance Survey (OS). While not the keeper of the land, the OS is the keeper of its memory, reminding us of these ancient trails that allow us to walk unchallenged across private land. I have friends who walk boldly as if England and Wales has full rights to roam and I wish I was more like that, but until such a time…

Footpaths are a great national asset. Walking with an American friend recently, I asked about their equivalent. She quipped about guns protecting private property while also having access to world-class national parks. But here, since buying and downloading the OS app, one great marvel is how close everybody is to striding out from their door and on to the network. Just this past winter, I discovered hidden valleys, towering woodland and lakes all within a handful of miles of where I grew up, having never known they were there. Without OS maps, would we remember the way?

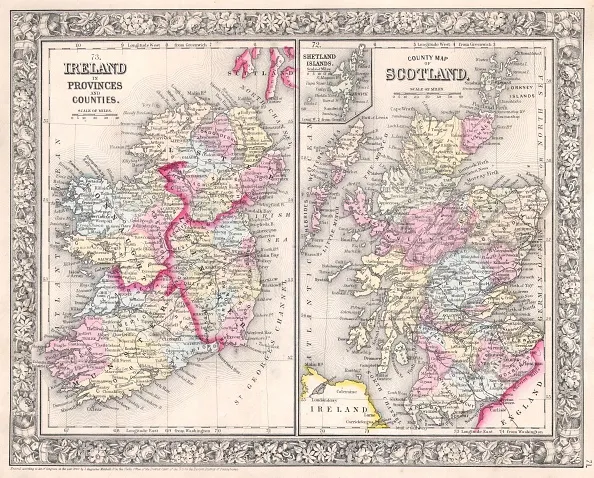

The OS was born out of a military need to map the Scottish Highlands in 1745, followed by the vulnerable southern coast, as a means of assisting moving troops and planning campaigns. A 21-year-old engineer called William Roy, using surveying compasses and 15-metre chains, completed the Great Map of the Highlands over eight years, and made it his lifelong mission to build a superior map of Britain.

The first maps available to the late-Georgian public were like works of art and expensive to buy – around one to three weeks’ wages – but were popular with landowners who could visualise an aerial view rarely seen before. The place names in early maps were sometimes challenging if local people didn’t agree on what a place was actually called. This was overcome by a Name Book system to mark down variations, and from this, the most authoritative were chosen for publication.

In 1824, the entire OS staff was sent to Ireland to produce an accurate map to support taxation. Soon after, similar detailed maps were in demand in England and Wales and with them, a new legal act giving surveyors the full right to roam.

With the outbreak of war, map-makers were sent abroad to plot lines of trenches and began to make use of new aerial photography, eventually printing 20 million maps to support the allies. A further 342 million maps were produced during the Second World War. From 1935 to 1962, the Retriangulation of Great Britain began, and thousands of concrete Trig Pillars were built on 4.5-metre foundations, which were dug by hand on blustery and soggy peaks throughout the country.

By the 1970s, digital maps were being produced, supported by photography and light-beam technology. In 1995, Britain became the first country in the world to complete large-scale electronic mapping. Today, up to 20,000 changes are made to the map each day. It is data, not owned by Google, that has enormous value for organisations that need to understand boundaries, postcodes, building locations, flood risk and for those of us in the country pursuit of walking.

These records are sacred documents, charting our rights of way across these lands. They remind us, not only of what a gift that is, but also to stop waiting for a weather window and to get our sorry a*ses out there.