I am haunted by the loss of wildlife – single trees, 10,000 trees, wildflower meadows and their worlds, spotted flycatchers, lapwings – the loss of a last nightingale. And I am simultaneously enchanted, thrilled, utterly seduced and filled with hope by nature. It moves me as much as any human relationship – now there’s a confession. But when did it all begin to mean so much to me? And why?

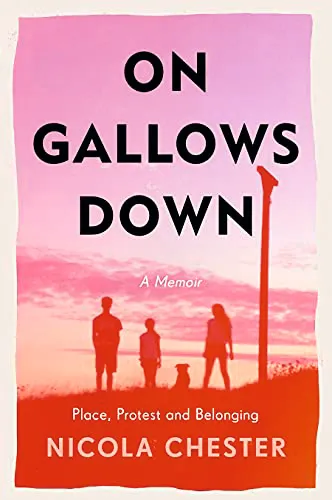

It took writing a book, On Gallows Down, Place, Protest and Belonging, to form a framework for the answer to these questions. Partly, nature means so much (and yes, as much as any human relationship) because the two are inseparable. We are nothing without nature because we are nature. And more than ever now, not to consider it in everything we do is to continue sawing off the branch we are sitting on. But also, as wife, mother, daughter, sister, friend (and all the other things we are), my very best memories and experiences with these relationships, these people, have happened in nature.

We are nothing without nature because we are nature

To see life through the prism of nature is everything. It is a way of belonging; of getting under the skin and history of a place, whether you come from there, farming generations deep, or whether you have just arrived in a place; whether you are a landowner, or own nothing very much at all – least of all land and a house. Nature is the state we are in, hope for the future and a way to survive. It’s why I write. Yet as soon as I remember consciously discovering nature, dawdling home from primary school the long way home, water-meadow mud oozing through my sensible brown sandals and up my socks like litmus paper, I knew loss. The rivers were poisoned of otters and the statuesque elms had been dying for a decade. I stacked the curves of their shed bark into little ‘libraries’, after poring over the linocut trilobite shapes left by the deadly, fungus-carrying, elm bark beetle. When we moved from that beloved place, it felt like a coming away of skin; a grieving.

Podcast: On Gallows Down: Tales of nature and protest with writer Nicola Chester

Roam Gallows Down on the Witshire, Hampshire, Berkshire border and hear tales of ancient and modern history – as well as the battles to defend the precious natural wonders of the area from new roads, American air bases and nuclear missiles. Author and activist Nicola Chester introduces Annabel Ross to the wonders of the North Wessex Downs.

Listen now

Then almost as soon as I ‘got into’ my new home (aged 11), making my acquaintance first through its woodlands and heaths, it was taken from me in dramatic fashion. A common enclosed in 1981 – Greenham Common in Berkshire, as it happens – which meant making room for 96 American nuclear warheads.

Inspired by the 19-year-long protest by the Greenham Women’s Peace Camp, I went on to join the road protests in the 1990s. Specifically, Newbury Bypass, which curved around my home, the rubble of the old Cold War runway at Greenham Common recycled under its tarmac. It destroyed my rural childhood playground as well as already threatened wildlife – and ignored the coming climate crisis.

That was 25 years ago and, however I can manage it, I have not stopped protesting the loss of wildlife and wild places since – or delighting in those things either, because that is as important.

I write in an attempt to engage and move people; to bear witness, make connections and hopefully, galvanise others to act – however they can. And activism for nature can be as simple as pointing out the character of an urban tree to someone; or appreciating out loud the value of a hedge full of berries left uncut.

Nature is how we belong to a place, too. Much of my book is centred on a small corner of the North Wessex Downs that Thomas Hardy and William Cobbett knew. A horseman’s tied cottage on the Highclere Estate (TV’s Downton Abbey) where my husband was assistant stud groom and we began family life. That continued (with another wrench) in a tenanted farmworker’s cottage on a next door-but-one estate on the high chalk hills – among the sometimes feudal mists of time and isolation, which I have a wry and hopeless love for.

Our rented cottage was built in 1952 for a new (or returned) generation of post-war farmworkers, by our landlord’s grandfather. In keeping with the other cottages and farm buildings, it was painted in the estate’s racing-green paint: even the stair carpet matched. Its thick, lined, well-appointed curtains are repeated in all six cottages.

On Gallows Down is a memoir of place as much as it is of a person. It’s an account of environmental protest, estate cottage living and the remnant rural working class. It’s about wildlife and living wilder. It’s an ecology of love, ruin and hope. It is witness to modern enclosure, women’s protest and the hard-won freedom of the commons. It’s about itinerant agricultural labourers and Romany travellers; a house and job lost because a mangel-wurzel was thrown at the landowner in half-starved anger. It’s also about the last of the nightingale torch singers, a smattering of ghosts, and hills as conductors of lightning and dissent.

It’s easy to romanticise rural life and its elegiac light that is, at times, timeless. Connections to the past, and new ways of looking at it are important – and skirt the often blind, exclusive and forgetful mire of nostalgia. But farming has always been about responding to the wider world and progress: landscape, climate, looking ahead, work and improvement. Of course, it doesn’t mean this is always good, or inclusive. But that’s where progress needs to be at now: a mutually supportive, welcoming engagement between farming and people.

And nature shouldn’t be exclusive to the countryside and those who live in it either – because it isn’t. We need greater, better and more inclusive access to nature, because everyone should be able to experience the benefits: and we need everyone involved if it (and we) are going to thrive. Habitats for nature should be part of our everyday lives wherever we live, work or go to school.

Belonging is as much about engagement, challenge, facilitation and claiming a place – leaving the gates metaphorically open for all. This isn’t easy for everyone, and we all have a part to play. Whatever place you are in now is the most significant point in its history, particularly at this time of wildlife and climate crisis. And if one person can be responsible for how a farm estate of thousands of acres is managed, why can’t each of us make a difference over what we ‘own’? And that could be our thoughts, speech and deeds, our campaigning power, the grass verge outside our home, a garden, a few pots, the way we shop and interact with others. This time, this place, now. We all belong to it.

Nicola Chester's book, On Gallows Down, is available now. Read our review

Main image credit: Nicola Chester on Gallows Down./Credit: Phil Cannings