Most people's knowledge of partridges starts and ends with the Christmas song "And a partridge in a pear tree". the partridge in question is the grey partridge, a small dumpy bird that has been part of the landscape of British Isles for millennia. However, If you see a partridge in a pear tree, do make sure you get a picture – partridges are famously ground-dwelling birds.

Our expert partridge guide covers key facts about the species, including diet and nesting habits, plus we discuss why the species is in trouble. Read on to find out all about their lives.

Grey partridge

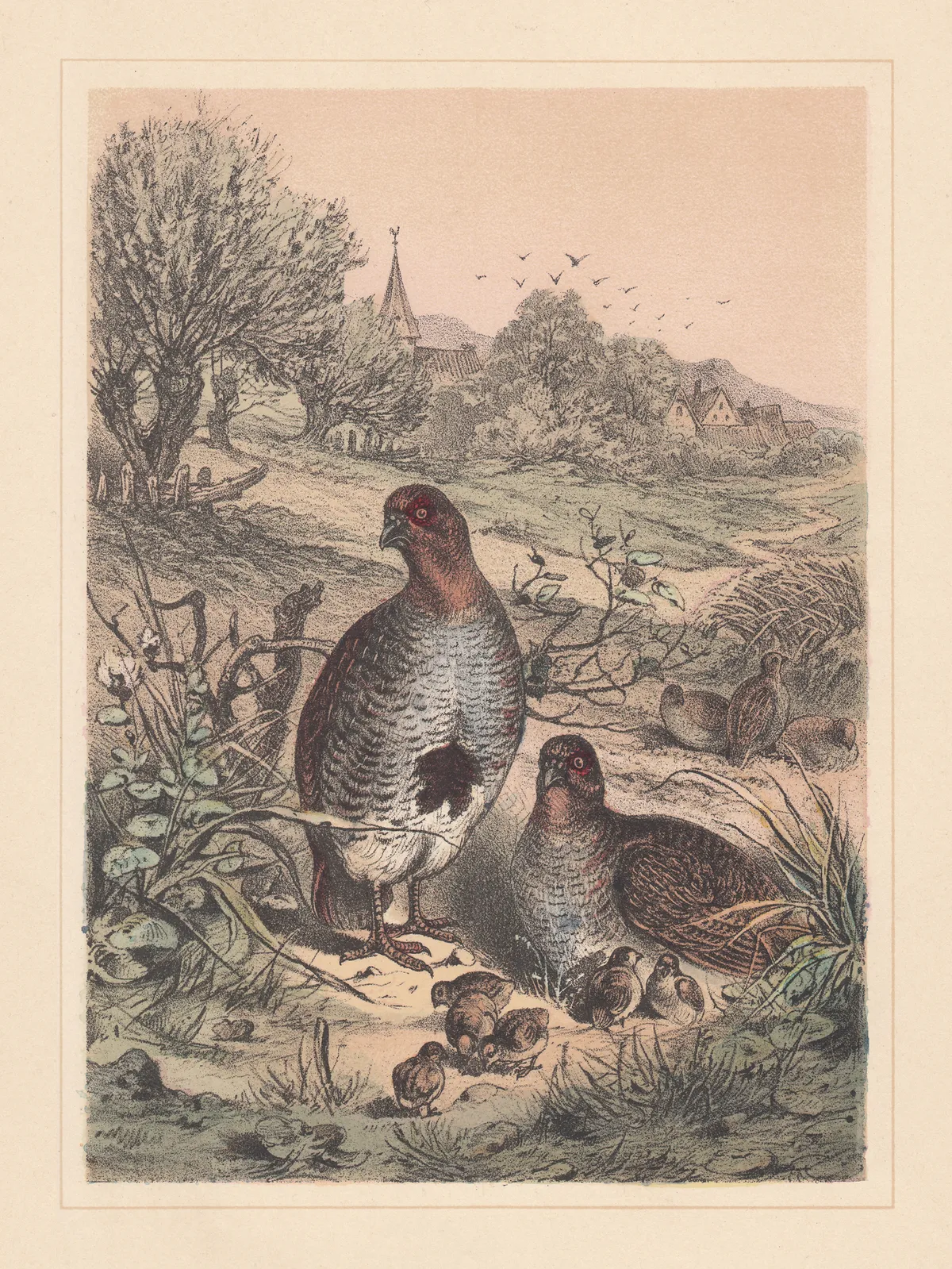

The grey partridge is a small plump bird, smaller than a pheasant. The face is orange but overall colouring is grey-brown with a distinctive the chestnut marking in the middle of the breast – this is much larger in the male. The male can often be seen standing while his hen – they pair for life – hunkers down next to him. Outside the breeding season, groups – or coveys – of 6-15 individuals form and stick close together, even in flight.

Where do grey partridges live?

In the UK, grey partridges are most numerous in central and eastern England. They are found in lowland areas on open farmland and pasture with occasional areas of bare earth that the birds use for dust bathing. They need hedgerows and dense cover for shelter and nesting – tending to make their nests at the base of the hedge.

One of the easiest ways to confirm that you’ve seen a grey, is the scratchy, cheeping call – kip-ip-ip – the grey makes on the wing. It also makes a distinctive, grating “ker-rick” call night and day.

What do grey partridges eat?

Grey partridges feed mostly on leaves and seeds but will eat spiders, insects and worms when they are foraging. Unlike other partridge species, greys tend to glean food rather than dig for it.

When do grey partridges lay eggs?

Grey partridges lay eggs in late April and May. The hen bird makes a shallow depression in the ground and lines it with grass. She then lays clutches of around 15 eggs – one of the most prolific layers of all British birds. Nests tend to be found in grassy margins, hedge bottoms, and rough corners. For the first three weeks of their life, a partridge chick survives on protein-rich insects. Accordingly, insecticides are bad news.

Both parents tend young and the male is particularly plucky. Cock birds have been recorded flying at weasels and stoats, while hens will feign a broken wing in order to draw away predators.

After an astonishing 15 days, the young can fly from danger but it takes 100 days to fully develop.

Why is the grey partridge in trouble?

There are thought to be fewer than 70,000 pairs of grey partridges in the UK, a decline of 80 percent since 1990. This is largely blamed on changing farming practices – the loss of wide field margins and hedgerows; autumn sowing of cereal crops which removes valuable stubble plus the increased used of insecticides and pesticides. For a while now, grey partridges have been recognised as a barometer species. When they do poorly, we know that agriculture is taking its toll and when they recover, it becomes clear that things are improving.

The Government is currently rolling out its new Environmental Land Management Scheme which will see farmers rewarded financially for facilitating wildlife recovery, which includes planting hedges and letting wild margins flourish. If, simultaneously, shooting estates implement grey partridge recovery plans and reduce the numbers of grey partridges that are shot, there could be better news for greys around the corner.

Find out more about grey partridges in our recent podcast with writer Patrick Galbraith.

Can you shoot grey partridges?

Although of grave conservation concern, the grey partridge is still shot in Britain – mostly in areas where its numbers are holding up. Shorting organisations publish rules for shooting the species – for example, the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust says “Do not shoot wild grey partridges if you have fewer than 20 birds per 250 acres (100 hectares) in the autumn. Below this level the population has little ability to compensate for shooting losses.” They also advise: “Do not shoot at grey partridges that are in pairs.”

Find out more about how shooting can support conservation.

Where can you see grey partridges?

Grey partridges are traditionally found in lowland arable areas of from the chalk areas of Wiltshire, Hampshire and Sussex, into East Anglia, Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire, reaching into the north of England and the East of Scotland as far as Aberdeenshire. They are secretive and their reduced numbers mean that it can be hard to spot them.

Red-legged partridge

Introduced into Britain in the 17th century for hunting, there may be up to 175,000 pairs of red legged partridges in the UK today but the number is hard to estimate as many millions are released from captivity each year for shooting.

Slightly larger than the grey partridge, the red-legged has attractive markings of white and chestnut on its flanks, a whit face with a bold black eye stripe and, of course, red legs.

It tends to be more visible than the grey, with males perching on vantage points such as gateposts or barn roofs – so if you're going to see a partridge in a pear tree in the UK, the red-legged is your best bet! Like the grey, it forms coveys outside of the breeding season of 30 birds or more.

Where does the red-legged partridge live?

The red legged partridge’s traditional home is southern France and Spain. In the UK it is found in the east and south, thriving in the wide open fields of modern arable agriculture, especially areas of light, sandy soils.

What does the red-legged partridge eat?

The red legged partridge eats leaves, seeds and roots, digging at the soil to get at tasty morsels. It will eat any insects it finds, especially when a chick.

When do red-legged lay eggs?

Red-legged partridges breed in April and May. Unlike the grey, it is the male who makes the nest, a series of shallow scrapes – and the female chooses one. She lays 10-16 eggs and may even lay a second clutch that the male incubates simultaneously (and each parents will look after their own brood of chicks). The young can fly even earlier than those of the grey partridge – at 10 days – but take 60 days to mature fully.