Worshipped as well as feared, Britain’s ancient yews are among the oldest living things on the planet. Tony Hall explores the roots of our deep fascination with these beautiful and enduring trees.

Learn about these impressive trees, plus discover the oldest yews to visit in the UK in our historic guide.

It’s the tree that can live forever, or so it’s said. No wonder that for thousands of years, the yew has been shrouded in myth, legend and folklore. In ancient times, the yew’s ability to retain its leaves through the cold, dark winter months would have been seen as almost magical.

More related content:

But unlike Britain’s four other native evergreens, the yew has a remarkable trait that even today is quite astonishing. A hollow yew is able to regenerate itself by producing new roots from its centre. These roots grow down into the ground to feed and strengthen the ageing tree, stabilising it and prolonging its survival, enabling the tree to continue life long after many other trees would have perished. With this exceptional quality, it is understandable that the yew was revered as a symbol of long life, rebirth and regeneration – and a fitting subject on which to focus in January, when our thoughts turn to new beginnings.

How to estimate the age of a yew tree

Many British yews are clearly extremely old, but when it comes to assessing the lifespan of these trees there has to be an element of ‘guesstimation’. The most accurate way to age a tree is by counting the number of annual rings in its trunk. But in old yews, the heartwood at their centre begins to decay when they are around 400 years old, leaving them hollow, and making an accurate count of annual rings impossible.

An ageing formula has been devised that involves measuring the trunk’s girth at a determined height – usually around one metre – over decades; this data is combined with known historical measurements, some dating back more than 300 years. But because of the unusual shapes of the trunks and the varying growth rates in different environments and parts of the country, this is also far from accurate, but is probably the best we can do.

Some have estimated that our oldest yews took seed a staggering 9,000 years ago. However, more recent research put this figure at between 2,000 and 3,000 years, which I believe is probably more realistic.

Which individual tree is the oldest of all? The jury is out. The most likely candidates are the Fortingall Yew in Perthshire and the Defynnog Yew – largest of four in the churchyard of St Cynog’s, in the Brecon Beacons National Park. Like these two ancient specimens, some of our oldest yews are found in churchyards; yet many are older than the churches standing nearby, and probably even older than Christianity itself. The association of yews with religion goes back to pre-Christian faiths: to the pagans who worshipped the natural world and the elements, including the sun, moon and trees.

A place of worship

The yew was a sacred tree, and sites with ancient yews became places of Druidic or Celtic worship. Druids, the priests of the Celtic tribes, believed wands of yew would banish evil spirits. When the pagan population was converted to Christianity from Roman times onward, the same sites continued to be considered sacred places. The Anglo-Saxons built churches near the old yews; later, the old churches were built over with new.

Historic yews

Over the years I have visited many of Britain’s oldest yew trees and have been truly amazed by their beauty, although not everyone finds that stunted hollow shell so attractive. Every yew tree is unique, and each has a story to tell. Many of these stories are recorded as myths and folklore, as with the Bleeding Yew of Nevern in the churchyard of St Brynach’s Church in Pembrokeshire.

As the name suggests, this tree continually exudes a sticky, red, blood-like sap. Some say this yew bleeds for the wrongful hanging of a monk, for a crime he didn’t commit. Another story is that it will continue to bleed until a Welshman once again sits on the throne at nearby Nevern Castle.

Britain’s most beautiful churches

Britain's peaceful rural churches are seeped in holy history and can be fascinating places to visit. Here is our guide to the UK's most beautiful rural churches, looking at the history of each, plus walks to interesting churches

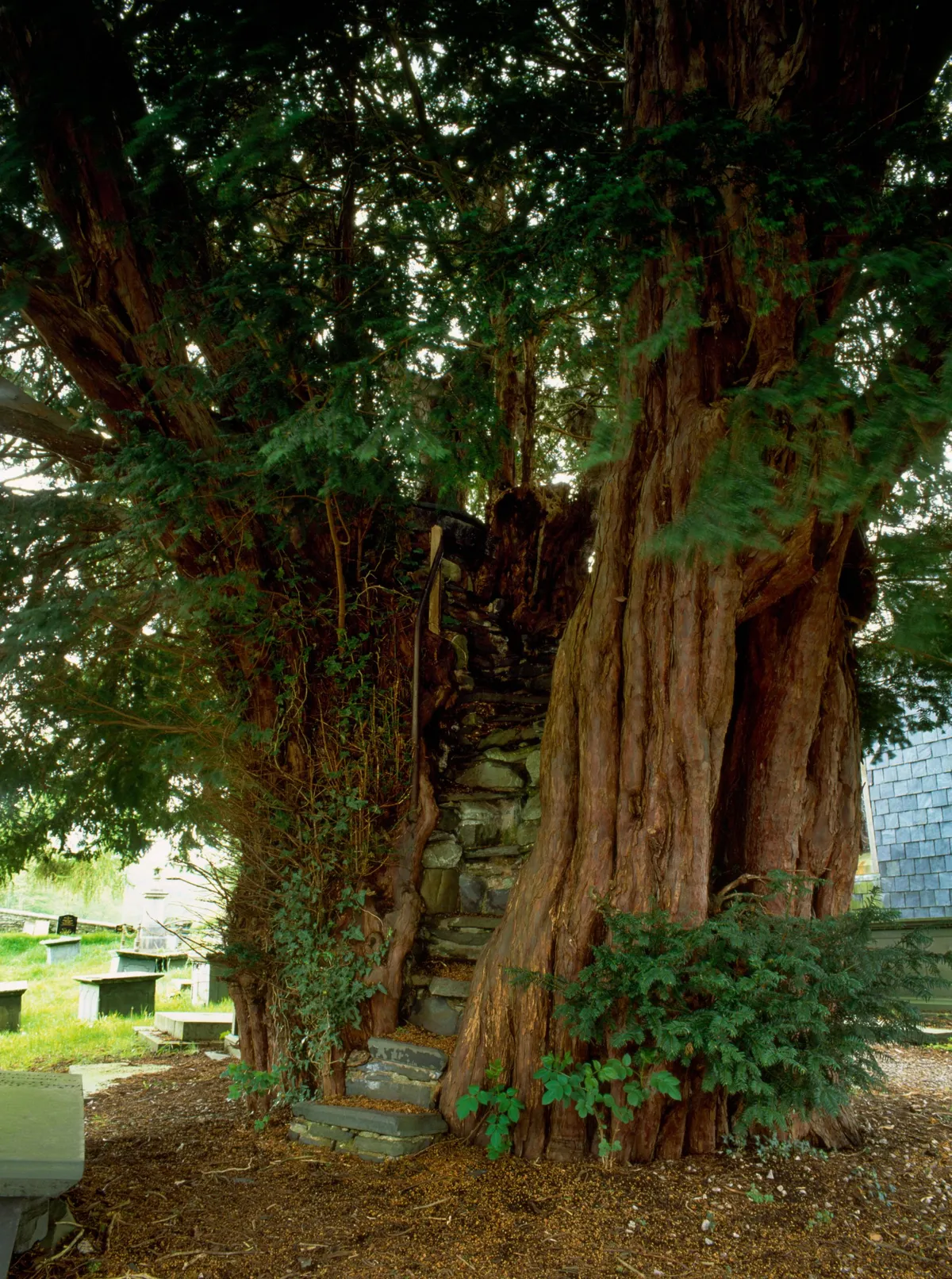

The extraordinary Pulpit Yew in Nantglyn, Denbighshire, hosts a set of slate steps with a handrail leading up to an area where it is said that open-air sermons could be preached. It is thought to have been used by John Wesley, the famous 18th-century Methodist minister

It was once widely believed that falling asleep under a yew on a warm day would bring on hallucinations, caused by the gases emitted from the leaves. Robert Turner, a 17th-century physician, believed the vapours from decaying bodies would gather under the branches of churchyard yews before they were imbibed by the tree, and that these vapours could be deadly to both man and beast. But in reality, there’s probably more chance of being hit by a falling branch during your afternoon nap.

Lethal weapons

Yew has been fatal in other ways, however – in the making of lethal weapons. One of the world’s oldest man-made wooden objects is yew: a spearhead, found in 1911 in Clactonon-Sea. This sharpened spike is an astounding 400,000 years old. Perhaps the best-known use of yew wood is in longbows, which are renowned for their great flexibility and power.

The oldest ever found in the UK was unearthed on the Somerset Levels in 1961. Known as the Meare Heath bow, it was created in the Middle Neolithic period, around 2,690 BC. Much later, yew wood was used by Norman archers to devastating effect during the Battle of Hastings in 1066 and during the great battles of the Hundred Years War (1337–1453).

When Tudor warship the Mary Rose was raised from the seabed in the Solent in 1982 – where it had lain since 1545 – archaeologists found 137 complete yew longbows and more than 3,500 arrows, mostly made of yew imported from Italy and Spain. But before the end of the 17th century, longbows were in decline as a weapon – outgunned by the musket.

The gardener's muse

Despite this martial use, for many of us, yew has a more peaceful association: with country gardens, where it can be cut and trimmed into a multitude of shapes and forms. The art of topiary goes back to Roman times, becoming popular during the Italian Renaissance from the 14th to 16th centuries, and during the 17th century in England. The gardens of Levens Hall in Cumbria still have original topiary

The Great Court at Athelhampton House, Dorset, boasts 12 perfect pyramid yews that dates back 300 years. Probably the tallest yew hedge in the world borders the boundary wall of the mansion of Cirencester Park in Gloucestershire. Other famous clipped yews include those growing in the atmospheric gardens of Powis Castle near Welshpool, Packwood House in Warwickshire and Athelhampton House in Dorset.

The poison tree

All parts of a yew are poisonous, except the red fruit known as the aril. However, the seed it cups is highly poisonous.

Birds find arils extremely attractive, particularly blackbirds, song thrushes and mistle thrushes, who eat the fleshy fruit but not the poisonous seed.

Badgers will also eat them; their latrines can sometimes be found full of undigested yew seeds. I have watched the non-native ring-necked parakeet discard the aril and remove the seed coat to eat the kernel inside, with seemingly no ill effect.

Caterpillars of the satin beauty moth are also able to tolerate the toxins in the leaves.

Hollows in yews make great nesting sites, while their canopies are often used as nests by goldcrests, the UK’s smallest bird.

While these clipped yews may be impressive and the huge churchyard yews have great impact, the yews that truly astound me are found in a completely different setting: woodlands.

Visit sites such as Newlands Corner in Surrey, or Kingley Vale in the limestone soils of the Sussex downland – one of the largest and finest yew forests in western Europe – to see these magnificent trees in a wilder environment.

If you are lucky enough to explore a yew woodland, look for ‘walking trees’. This fascinating phenomenon occurs when the lower branches of the parent tree hang so low that they take root in the soil and eventually grow into new trees. The process of layering and rooting then continues, as new trees take root further and further from the parent tree. This is just one more example of the yew’s incredible ability to regenerate. But despite this natural vigour, the future of many of these ancient yews is increasingly uncertain.

While Britain’s yew trees have so far demonstrated a remarkable talent for survival over hundreds or even thousands of years, the advent of climate change poses fresh dangers. Yews have shallow roots that may not cope well with the warmer and drier conditions expected. But who knows? Maybe global warming will be just one more challenge for these amazing living relics to overcome.

For more information about ancient yews near you, go to ancient-yew.org

Where to find Britain's oldest yews

Ankerwycke Yew, Runnymede, Surrey

Thought to be around 2,500 years old and with connections to the Magna Carta, this is the oldest tree on National Trust land. It was already an ancient tree when the oaths were signed in 1215.

Borrowdale Yews, Cumbria

William Wordsworth immortalised these yews as the ‘Fraternal Four’ in his 1803 poem. Unfortunately, only three now remain. Park at Seathwaite Farm (grid ref NY236 123); the yews lie north of the farm and are marked on OS maps.

Crowhurst Yew, near Oxted, Surrey

This fantastical photogenic yew in the churchyard of the hamlet of Crowhurst has a hollow trunk once said to have been a meeting place, fitted with a table and bench.

Defynnog Yews, near Sennybridge, Powys

The four yews that surround the church of St Cynog are all of great age, but is the largest of them on the north side the oldest tree in Europe? The jury is out.

Fortingall Yew, near Aberfeldy, Perthshire

Scotland’s oldest tree is estimated to be anywhere between 2,000 and 9,000 years old (the lower estimate being more realistic). This male tree made headlines for its ‘sex change’ when one of its branches became female and produced berries.

Kingley Vale Yews, near Plumpton, West Sussex

The enchanting woodland of Kingley Vale is one of the largest and finest yew forests in western Europe. Walking among the arching tunnels formed by these magical yews is the most extraordinary experience.

Linton Yew, near Ross-on-Wye, Herefordshire

This ancient bulging hollow trunk presents perfectly the yew’s power to regenerate. An aerial root put down many years ago is now ready to take over from the parent tree, should it fail.

Newlands Corner, near Guildford, Surrey

In this open yew woodland above the North Downs, the yews form fascinating shapes, with many displaying bulging waistlines that I have termed ‘the Pot-Bellied Yews’.

Totteridge Yew, North London

The Totteridge Yew is the oldest living thing in London, originally growing between two Roman roads. The tree’s girth has changed very little since its first recorded measurement in 1677.

Ulcombe Yew, near Maidstone, Kent

With a girth of around 10m (33ft), this is one of the largest British yews. A brass plaque at its base states: “This yew is said to have stood here since before the birth of Christ.”

Tony Hall is senior arboretum and gardens manager at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and author of The Immortal Yew (Kew Publishing, £25)