Our guide on how to identify British wildflowers, with a few key details about where to find them and when they're in bloom.

Why are wildflowers important?

Swathes of wildflowers not only look beautiful, but they also provide food for pollinators such as bees throughout the seasons. These in turn pollinate vital crops such as fruit and vegetables. Wildflower meadows also offer shelter for pollinators to breed and, once established, can help nutrients to remain in the soil during heavy rainfall.

Where do wildflowers grow?

Wildflowers can be found growing all over the UK and in a range of different habitats. Despite common perception, they can also grow in shaded areas such as woodlands.

When do you plant wildflowers?

Seeds are best sown during March and April and they should germinate quickly.

January

Snowdrop

The snowdrop may appear delicate but it is a hardy little plant, surviving snowfall and cold temperatures. It has long been associated with the winter – its Latin classification, Galanthus nivalis, literally means ‘milk flower of the snow’.

In the 1950s, snowdrops would not typically flower until late February, but during the past few decades the teardrops of white have appeared ever earlier, and in particularly mild winters, snowdrops may not even wait for a New Year to begin.

When formed, the flower hangs from the stem like a lantern on a ship’s bow, with the three outer tepals curved into a tight pointed oval that may appear solid. However, there is plenty of room for an insect to squeeze its way in and find pollen at a time when other food is scarce. The bracts later open, releasing the flower to droop downwards, with three outer tepals opening outwards and three inner tepals (white and light green at the tip) remaining close together.

Snowdrops guide: best snowdrop walks in the UK and how to grow

After the darkness of winter, snowdrops are a welcome and early sign that spring is on its way. Our snowdrop guide looks at the best snowdrop walks in the UK, snowdrop facts and how to grow your own

Discover the best snowdrop walks in the UK

February

Lesser celandine

Wordsworth wrote famously of the daffodil, but it was a smaller, more reticent yellow flower that truly captured his poetic heart: “There is a flower that shall be mine, ‘T is the little Celandine.”

We have two flowers with the name celandine, the greater and lesser, though they are neither closely related nor strikingly similar in appearance – save the yellow of their flowers. Wordsworth’s inspiration was the earlier-flowering lesser celandine, whose heart-shaped leaves are among the first greens to slip between the tired pastels of late winter. They keep a low profile away from the bite of the wind, and often go unnoticed until the flowers unfurl.

The shape of the tubers has been likened to a bunch of figs, hence the Latin name Ficaria, whereas in the late Middle Ages, another similarity was noted. The doctrine of signatures was widespread, suggesting a plant could be used to treat the body part it resembled. This led to the naming of flowers such as eyebright, lungwort and hedge woundwort. The tubers of lesser celandine were considered to resemble haemorrhoids and the plant was applied accordingly, becoming popularly known as pilewort.

Perhaps a more poetic and less unpleasant association may be taken from the source of the word ‘celandine’, which is derived from the Latin Chelidon – a name given to the swallow, long considered a herald of spring.

Alexanders

The green umbels of alexanders have a musty smell that attracts fly pollinators. A former herb, it fell from favour after celery was introduced. It’s now naturalised near the coast.

Wood sorrell

Its nodding flowers may be marked with pink veins and yellow spots at their base. Wood sorrel often grows over decaying branches on the woodland floor.

Butterbur

Underground rhizomes produce conical pink inflorescences that erupt through riverbank soil before the leaves expand. It has separate male and female plants.

It is a short to tall, hairy patch-forming perennial. Its leaves are rounded-heart-shaped, grey-hairy beneath and are often very large and irregularly toothed. Its flower heads are pale reddish-violet and unscented, with the male larger at 7-12mm and the female 3-6mm, borne in cone-shaped panicles.

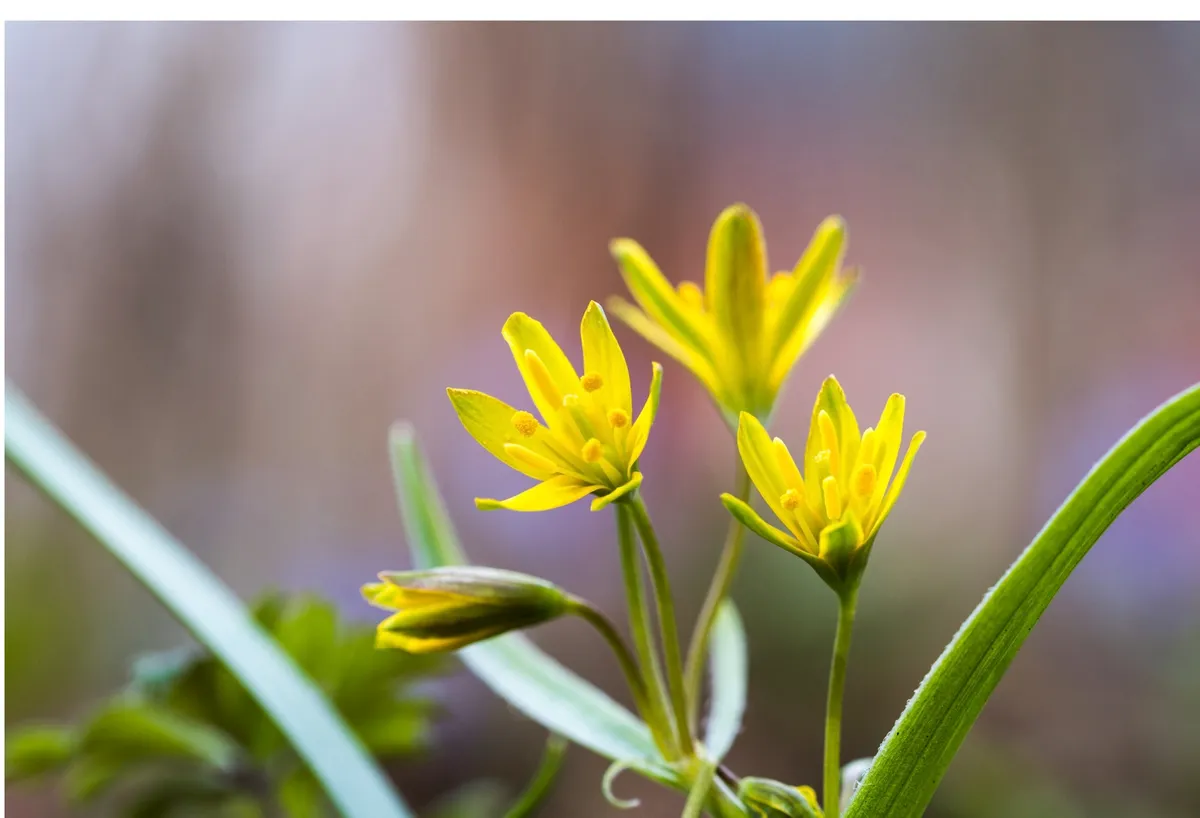

Yellow star of Bethlehem

One of many yellow British wildflowers, the yellow star of Bethlehem has green-backed petals which open to reveal umbels of blooms that are easily overlooked among the lesser celandines. It is locally common on limestone soils.

Sweet violet

The only native violet that’s fragrant, this is always the first to flower. Creeping stolons root at their tip, so old plants form large patches in hedgebanks. Sweet violet is also commonly known as wood violet.

Spurge laurel

Clusters of scented green flowers on this evergreen shrub attract the first bees and brimstone butterflies. It can be found in calcareous soils, in hedge banks and beech woods.

March

Wood anemone

Dominant in March are the distinctive leaves of the wood anemone. These are palmate in shape and slightly reminiscent of flat-leaved parsley, although their odour should prevent any herbaceous confusion. Their musty waft is not unlike the musk of a fox, leading indeed to the local name ‘smell fox’.

A more familiar sobriquet is ‘windflower’, particularly in a historical context. The Roman scribe Pliny wrote of this delicate flower in his Natural History, suggesting that it was so named because it will not open up its petals until the wind blows. Though this is a slightly unsatisfactory explanation, it does allude to the sensitivity of the wood anemone in relation to the weather. During heavy rain, or as dew threatens at dusk, the linen white sepals of the wood anemone fold shut and the flower droops over like the head of a scolded puppy. This process helps to protect the delicate stamen and immature seed-heads within.

Kingcup

Kingcups are also known as marsh marigold – the term marigold came about when it was used in church festivals in the middle ages, as a devotion to the Virgin Mary. They thrive along streams and in shallow water around ponds, forming loose clumps of leaves in early spring and flowering in early summer.

April

Dandelion

The dandelion responds each day to the warmth of the sun, splaying open ligulate petals and pushing its stigmas skyward. The flower head then follows the sun west before closing at dusk – tightly packed like a paintbrush dipped in butter.

Luckily the dandelion is one of the most common wildflowers – it is rich in nectar which makes them a popular food source for insects. The pipe-like stalks are hollow and contain a latex milk once believed to cure warts.

The toothed leaves may be eaten as a salad plant, especially when young, but their astringency does not appeal to all tastes. They are rich in vitamins A and C, while the shape is believed to be the source of the plant’s etymology – the French term 'dent de lion' literally meaning 'lion’s teeth'.

The most versatile part of the dandelion is surely the root. It is used in beers and cordials, often alongside that of burdock, while if dry-roasted and ground it offers a surprisingly tasty alternative to coffee. This drink may be caffeine-free but might still wake you up at night as the dandelion often has a diuretic effect. They have also been long-used in wine making.

Forget-me-not

This blue-hued flower's common name comes from a German romantic tragedy – where a man falls into a fast flowing river while on a stroll with his lover. While being swept away he throws a bouquet of these flowers at her, shouting, “Forget me not!” Perhaps fittingly, they are commonly found growing near brooks and streams. They can also be identified by their five petals on each head and yellow centres.

May

Bluebell

The stem curls beneath the weight of a dozen bell-shaped flowers, each one formed from six lobes that curl back to expose the anthers. The flower is smooth and unmarked, a quality that led to its Latin etymology.

When Carl Linnaeus was classifying the flower in the 18th century, he referred to Romano-Greek legend for inspiration. After the hero Hyacinthus fell, Apollo took his blood and with it created a flower. The god wept, and his tears marked the newly formed petals, resulting in the naming of the genus Hyacinthus.

The perfume of the bluebell can be intoxicating, though it is a smell under threat. The non-native and almost odourless Spanish bluebell has spilled from gardens and parks, hybridising with our native bluebell and neutralising May’s traditional woodland waft.

Dog rose

The white and pink-hued flowers have five delicate petals to them, but it has curved prickles on its stem to help it climb. It was thought that dog rose (or Rosa canina) could treat the bite of a rabid dog, giving a possible explanation for its name, in the 18th and 19th century. It can commonly be found in hedgerows or grassland.

Columbine

The columbine, or Aquilegia is part of the buttercup family. There are many different varieties which vary in colour, but the columbines found in the wild often have rich violet-blue nodding heads.

Water avens

As befitting to its name, the Water avens is commonly found in damp habitats such as riversides and wet woodlands. It can be easily identified by its purple and orange nodding heads on purple stems. The roots of this plant have many medical uses due to them containing high amounts of tannins; the root can also be used as an anti-inflammatory and antiseptic.

Scarlet pimpernel

Best known as the emblem for the famous fictional character in Emma Orczy’s first novel, this British wildflower is probably our most pleasant weed. It is easily identifiable by its red flowers, but they can sometimes be blue, which close up in bad weather. This means they can thrive in harsher environments such as coastal cliffs and chalk downlands.

Ragged robin

'Flos-cuculi' (from its Latin name Lychnis flos-cuculi) supposedly means 'flower of the cuckoo', named as the first flowers of the ragged robin appear just as the British cuckoos are first heard in May. It it pale to bright purplish-pink in colour, occasionally white, with the petals cut into four divided segments. They also thrive in damp habitats.

June

Red campion

The red campion is common across much of lowland Britain and is dioecious, meaning the male and female flowers form on separate plants. As a result, they are heavily reliant upon pollinating insects in order to reproduce. The plants are without scent, so insects must be attracted purely by colour. Although the flowers are relatively small (normally less than 25mm in diameter), the plant itself is fairly prominent, often growing in excess of 60cm high. The stem is stiff and hairy, with pairs of heart-shaped, ivy-green leaves, sparingly placed. The roots contain saponin and were once boiled to form a substitute for soap.

On the Isle of Man, the plant is known as 'blaa ny ferrishyn', meaning 'fairy's flower', due to the traditional belief that fairies used the red campion to guard stores of honey.

The flower has long been associated with snakes, presumably because it grows in areas where reptiles may frequent. In Wales and parts of south-west England, red campion is historically bound to the adder, with a common belief that the seeds, when crushed, form a successful anti-venom. Other people, meanwhile, feared that a snake would bite anyone who dared to bring a red campion into their home.

Enchanter’s nightshade

The botanical name of this wildflower (Circaea lutetiana) is named after Circe, a witch from ancient Greece, who notoriously turned men into animals. It is easily identifiable because of its tiny white flowers, which bloom from pink buds. It can be found in hedgerows and woodlands.

Honeysuckle

The flowers have a distinctive, slender form, and encase a tube that stores the ambrosial nectar. Dormice are particularly fond of eating the energy-rich flowers and will also use the bark of the honeysuckle to line their nests.

The leaves are paired and oval in form, and provide food for the caterpillars of the white admiral butterfly. The larvae feed hard as the days shorten, before, as the temperature falls, securing a leaf to a twig with silk and curling up inside until spring.

The stems are lithe and flexible and entwine themselves around saplings or branches, a characteristic that led to the plant’s traditional association with courtship and devotion, often reflected in romantic literature.

As October passes, the final few honeysuckle flowers fade, replaced instead by tight clusters of berries that ripen into deep red. Blackbirds and winter thrushes gorge on the fruits’ sticky flesh but pass the seeds, aiding the plants dispersal.

Cornflower

In folklore, young men who believed they were in love wore these flowers, and if the flower faded quickly it represented that their love was not returned. Cornflowers are actually composite heads of smaller flowers, which become even smaller and take on a more purple hue in the centre.

July

Hogweed

A perfume need not be particularly pleasant to be evocative, and few smells seem to suit the heavy air of high summer like the pungent waft of hogweed. The odour has been likened to that of a pig, as its common name would suggest, and attracts myriad pollinating insects even though our own noses may be turned.

The small white flowers are numerous and variable in size. They sit upon umbels that grow upon multiple rays, splaying out from the stalk like the upturned legs of a spider.

Hogweed is similar in appearance to several other plants of the carrot family, and thrives in the same habitat. It is, however, larger and more robust than cow parsley and rough chervil. Its size and form led to its Latin classification; Heracleum deriving from the Greek hero Heracles, while Sphondylium relates to the segmented stem.

Like much of the plant, the thick, hollow stalks are edible, and were once used as pea-shooters by playing children. Care should be taken when near hogweed – it is easily misidentified as the highly poisonous hemlock and cowbane.

As the leaves photosynthesise, hogweed releases a sap that can cause irritation to sensitive skin. In recent years, its more dangerous, non-native relative, giant hogweed, has spread through the UK. The secretion from this huge (up to five metres tall) invader reacts with sunlight and can cause burns and permanent skin damage.

August

Ling heather

Ling is the most common of our native heather species and also the latest to bloom. The flowers are small and abundant, but less distinct in form than the tight bell shape of other heathers. The mauve colour may vary in tone, while occasionally the flowers are pure white.

Scottish legend tells of Malvina, daughter of the third-century poet Ossian, who was presented with a sprig of purple heather picked by her dying love, the warrior Oscar. Her tears fell upon the ling, and the flowers – so tortured by her grief – turned white. Despite this tragic association, white heather has long been regarded as a token of good fortune, while some believe its presence marks the place at which a fairy came to rest.

Ling is especially widespread in Scotland where it has been utilised both practically and culturally. When dried, it was once used for filling mattresses, while the short, stiff branches would be made into brooms, a quality that led to the Latin name Calluna – derived from ‘kallunein’, Greek for ‘cleanse’ or ‘sweep clean’.

The sinewy twists are toughened after many seasons of exposure, cropped by the wind and tightly bound against the rain. A plant may live for 40 years, supplying food for myriad pollinating insects. The flowers are also used for winemaking and beer brewing, while the seeds and shoots provide vital sustenance for deer, hare and birds such as ptarmigan.

September

English stonecrop

Our rocky, salt-scoured coastline is an inhospitable and unforgiving environment, particularly in the west, where the sea is so often stirred by prevailing winds. Here, few species of flora cope with the conditions, yet one or two hardy little flowers thrive.

One of these is the English stonecrop, a slight misnomer as it is found throughout the British Isles. Stonecrop prefers to root in acidic soil, but is not too fussy and will find a foothold in the narrowest of cracks. The small, teardrop-shaped leaves alternate on the stem, with each bulbous form storing precious reserves of water.

To negate the constant buffeting of the wind, stonecrop keeps a low profile, hugging the ground and rarely exceeding a few centimetres in height. Instead, it creeps across the rock surface, creating a dense blanket of rose-tinted green.

Stonecrop is a lover of the sun, and waits until the days are at their longest before flowering. The five lanceolate petals and rounded carpels are white when first formed, but soon begin to take on a pinkish hue. The flowers are small and will still be showing as summer passes into autumn.

Though primarily associated with the coast, stonecrop is also found inland, forming carpets across the rugged and weather-beaten landscapes of Snowdonia, Cumbria and western Scotland. Elsewhere it is more scattered, but as a perennial popular among gardeners, it may be found in naturalised pockets almost anywhere.

The stonecrop’s ability to cling to almost vertical surfaces has recently been utilised in the construction of ‘green’ housing. As a living roof, the tightly packed leaves provide a buffer against extremes of weather and a natural source of sound insulation.

November

Poppy

Late autumn is a time of muted colour. Leaves lie brown on the forest floor, while the once-green verges are lost beneath a march of deadening nettles and dried hogweed. As the days shorten, few flowers are willing to brave the approach of winter, yet it is this time of year that we associate with one of the most striking blooms of all. By November, the delicate red flowers of the poppy will have disappeared from our meadowlands, but the seed heads will be scattered across the ground, where they may lie dormant for decades.

Each chambered capsule can contain thousands of tiny, black seeds – familiar as a topping on bagels or bread. They will remain encased beneath the earth, relying upon a disturbance of the soil to break the capsule and scatter the robust seeds.

This quality has led to the familiar appearance of poppies on cultivated farmland, though they do not blanket the countryside in the numbers they once did (despite an ancient association with agricultural fertility, the poppy can be mildly poisonous to grazing animals and is widely regarded as a weed species).

Bursts of colour still occur here and there, particularly on wasteland or field edges, but it is in November that the deeper symbolism of the poppy comes to light. As bullets flew and shells fell during the First World War, countless trenches and graves were dug, disturbing millions of poppy seeds from their slumber.

The subsequent sight of the flowers swaying among the graves of the dead inspired John McCrae to pen In Flanders Fields. The poem did much to establish the poppy as a symbol of remembrance for the fallen.

December

Ivy

As autumn drifts into the dark of winter, the once-busy buzz of insect life reduces to little more than a gentle hum. Food is scarce now, but the final few flowers of the ivy still provide a source of nectar. Wasps and hornets will be flitting around the dense green-white umbels, while blackbirds and thrushes feast upon the first of the tight-clustered berries.

Ivy is often regarded as a parasitic plant, but it sources nutrients and water through its own root system, even if it relies on assistance for physical support. It will often climb trees, though never quite to the top – the dense foliage around the crown of the host prevents sunlight from reaching the ivy beneath, and instead of climbing further, the plant will settle and then mature.

As the stems intertwine, the leathery leaves form a thick evergreen shield, beneath which water and light struggle to penetrate. Here, the temperature range remains tight, and throughout the year woodlice and spiders scuttle through the shady must, while tawny owls slip in before dawn after a night of hunting.

Ivy has long been associated with Christmas, a link likely adopted from the pre-Christian age when sprigs were brought into homes to ward off evil spirits. In Ancient Rome, meanwhile, the plant became associated with a different type of spirit. When worn on the head, ivy was thought to temper the effects of alcohol – Bacchus, the Roman God of Wine, is often depicted wearing a crown of ivy.