Initial numbers from the National Trust’s five-yearly puffin count on Northumberland’s Farne Islands have reported a 12% fall since 2013, when nearly 40,000 breeding pairs were recorded. On one of the islands, the population may have dropped by as much as 42%.

The iconic seabird has also returned to the islands four weeks later than normal due to a harsh winter conditions.

“Initial findings are concerning. Numbers could be down due to stormy or wetter weather as well as changes in the sandeel population, which is one of their staple foods,” said ranger Tom Hendry.

“So far we’ve surveyed four of the eight islands where we conduct the census. Figures from the two largest islands are vastly contradictory with numbers on Brownsman 42 per cent down, while recordings on Staple show an 18 per cent increase. We will now do some further investigations as to why this might be.

“Figures across the two smaller islands are more consistent, but numbers are still down by up to 33 per cent. We will hopefully have a much clearer picture towards the end of the count in late June.

“If the final results reflect this drop, this will increase the need for us to monitor these beautiful ‘clowns of the sea’ more frequently.

“Puffins are notoriously difficult to monitor which is part of the reason why they have not been monitored every year. Annual monitoring will help us discover the true picture and help track numbers against likely causes of population change, whether the causes are found to be changes to the weather as a result of climate change, changes in the sandeel population or something else altogether.”

Puffin populations on the Farne Islands have been observed since 1939 when just 3,000 breeding pairs were recorded. Every survey since then showed a steady increase, until 2008 when numbers fell by a third, from 55,674 to 36,835.

Reasons for the decline in puffins are thought to include: climate change, leading to food shortages and extreme weather, overfishing, marine pollution and invasive predators such as rats.

In 2015, the Atlantic puffin was given ’vulnerable’ status by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The puffin is also on the British Trust for Ornithology’s Red List for species of conservation concern in the UK.

The National Trust rangers live on the islands from March to December, monitoring the puffins and other wildlife.

“The first thing we do is arrange a grid over the most populated islands to determine the best locations to put at least 30 plots per island. This ensures we cover different habitat types and keep our plot selections random to reduce statistical error,” said ranger Harriet Reid.

“We then put a stake in the middle of each plot and put a piece of string 5m long out, and use that diameter to check all the burrows around the central stake. We will also do a full census on the least populated islands, looking at every burrow.

“We’ll be looking out for the first birds with fish in their beaks, a sure sign their burrows are occupied with a hungry puffling. We also look for external signs around the burrow to determine whether puffins are using it, such as fresh digging, puffin footprints, clearance of vegetation at the burrow entrance, hatched eggshells, or fish or guano in the entrance. If we are unsure, it’s only on this occasion that we’ll put our arm down the burrow to gently and carefully feel for any occupants. We then carefully record our findings.”

“Predictions have been made that within the next 50-100 years these stunning birds will have completely died out on the Farne Islands. The Icelandic population in particular is really struggling, with exceptionally low productivity for over ten years.

“The monitoring of puffin numbers worldwide is therefore really important to discover whether the species can continue to survive. If we can carry out an annual census, in as many places as possible, this will give us more of an indication as to what is impacting these truly special birds – and give us insight into what else we can do here, at other sites across the world, to help the species.

“If the causes of puffin decline are what we suspect, it will require a bigger effort to encourage everyone to think about how we can prevent overfishing, reduce our use of single use plastics and limit our use of non-renewable energy, but it can be done.” Tom concluded.

This year also marks the 25th anniversary of the Farnes achieving National Nature Reserve status. Find out more about the islands here.

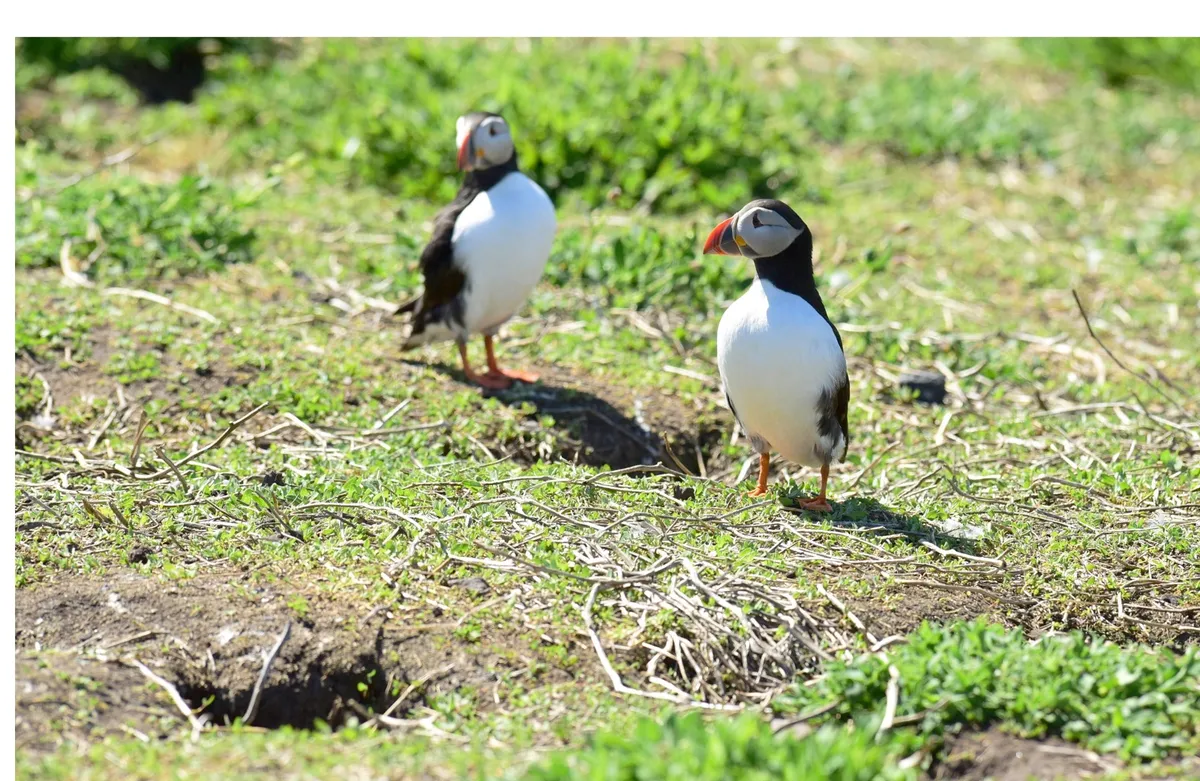

Main image: Puffins on the Farne Islands ©Paul Kingston and NNP