It is almost impossible these days to imagine how common the corncrake (Crex crex) once was in Britain. It bred all over the country and its loud call was a familiar sound to everyday country dwellers. It was so numerous that people used to eat it.

Now its population is a barely a shadow in comparison. There is perhaps no more evocative symbol of a long-vanished and less complicated world.

In this species guide, we take a closer look at the corncrake, revealing what they look like and sound like, where they live and what family of birds they belong to.

Interested in learning more about British wildlife? Check out our guides to ducks, wading birds and reptiles.

Rails, crakes and coots

The rail family includes moorhens, coots, water rails, corncrakes and spotted crakes. Find out more about these characterful birds with our spotter's guide.

What is a corncrake?

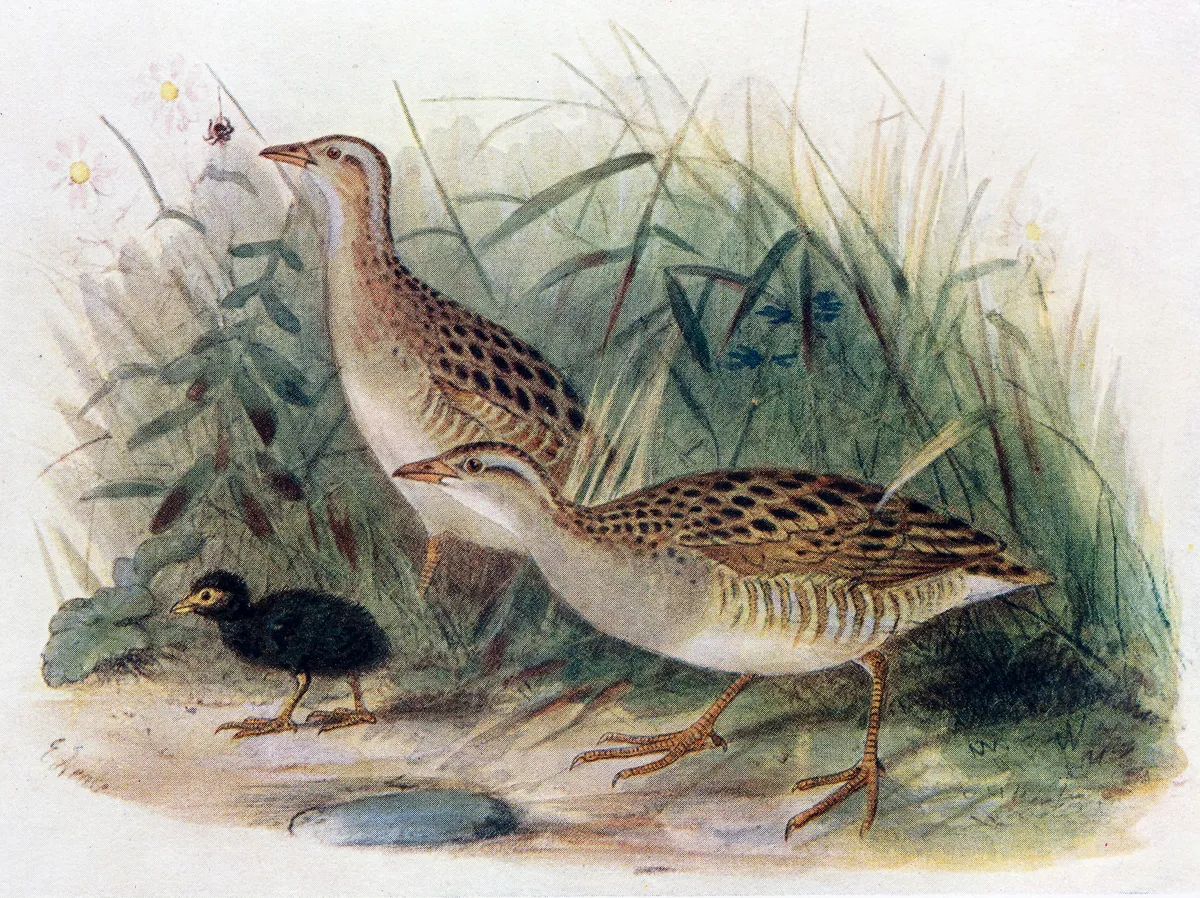

The corncrake – Crex crex – is a warm brown rail with rich chestnut-brown wings and short, stubby bill. It measures 27-30cm in size. It's an extraordinarily elusive bird, able to slip easily through dense vegetation and out of sight.

Despite its short, rounded wings that make its flight look weak, it is a long-distance migrant, spending the winter in Africa south of the Sahara.

What does a Corncrake sound like?

You might have noticed that the scientific name is “Crex crex”, and this is an excellent description of the spring song, which can be heard day and night.

You can imitate it by drawing the teeth of a comb over a full matchbox, but then imagine it much louder.

Corncrakes are adept at throwing their voices, and they plague birdwatchers by appearing to be very close one moment but far the next.

Podcast: sound of a corncrake

Join naturalist James Fair on the Hebridean island of Tiree as he goes in search of the corncrake with local expert John Bowler of the RSPB.

Where do corncrakes live?

In contrast to our other rails, the corncrake is much less of a waterbird, associated with meadows, fields and pasture. It nests in great secrecy on the ground.

Corncrake distribution in Britain

The machair grasslands of the Inner Hebridean island of Tiree are the corncrake’s stronghold, and you have got a high chance of hearing one there between May and August. The primary reason for the corncrakes decline was agricultural changes, particularly the shift from late hay-cutting to early cut for silage, along with mechanisation of mowing. It thrived when hay was cut by scythe, and today only flourishes where such practises are still carried out, such as in the Hebrides.

It is still found in parts of Scotland and Ireland and has been reintroduced to the fenlands of Eastern England. Only intensive conservation work keeps it going.

The UK is home to 1,200 breeding pairs of corncrake (0 in winter). They are listed as rare and are on the Red List of Species of Conservation Concern.

Corncrake video

Please note that external videos may contain ads:

Corncrake singing in spring/Credit: Wildlife World

Where to see corncrakes

Sadly, corncrakes have been reduced to a few strongholds in western Scotland, with a handful of introductions in England. These are some of the best sites to see corncrakes today in the UK.

Tiree, Inner Hebrides

This is the corncrake’s British stronghold, with around 300 calling males found throughout the island. The pastures between Balemartine and Balephuil in the south are recommended.

Coll, Inner Hebrides

Listen for the bird at Coll RSPB Nature Reserve, which is towards the south-west of the island.

North Uist, Outer Hebrides

Balranald RSPB Nature Reserve, on the west coast, is managed using traditional crofting techniques, and the small fields around the visitor centre attract corncrakes.

Isle of Skye

The RSPB advises that areas around Trotternish and Waternish are best for hearing corncrakes, though the population on the island is still quite fragile.

Welney WWT, Norfolk

A captive-breeding and reintroduction programme managed by Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust and Pensthorpe Conservation Trust is having some success. At least six males were recorded at Welney in 2022.

What do concrakes eat?

A wide range of invertebrates, including many different types of insects, spiders, slugs

and worms – as well as seeds.

When do corncrakes breed?

They arrive back in Britain in mid-April. Although rarely seen, the males fight each other over females. They flutter up into the air, scrabbling at each other with very sharp claws

Females produce their first brood of chicks by late May to mid-June. They will then have a second brood, and even – if time allows – a third. Females typically lay between six and

10 eggs. Incubation takes up to 19 days. Chicks are looked after for 14 days after hatching and fully fledge after 34–38 days.

How long do corncrakes live?

They are short-lived birds – most will only make it back to Britain for one breeding season. Some calling males have been recorded for three years.

Where do corncrakes migrate from?

Until scientists started radio-tagging corncrakes, we knew next to nothing about them. Now we understand how British corncrakes migrate to the Congo Basin via West Africa (unlike many continental corncrakes, which overwinter further to the south and east) and also how they behave when they are here, but it’s taken months of fieldwork and a lot of ingenuity to discover this much.

It’s only really through the declamations of the crexing males that we know they are around at all, and even their arrival (April) and departure (usually in September) is largely unseen.

“We do know they arrive and leave by night,” says the RSPB's John Bowler. “A colleague was counting seabirds one night, and they came towards him, flying like bricks. He wondered what these fat little birds were, then they dropped down on the headland and he could see they were corncrakes. That’s the only time I’ve heard of people seeing them flying in from migration.”

Why have corncrakes declined?

To understand what has caused the corncrake's precipitous decline, we must go back to a research paper written in 1944 by an ornithologist called Tony Norris. Norris showed, through correspondence with people throughout Britain, that corncrakes started disappearing from the south-east of Britain in the 1880s and 90s and that it coincided almost perfectly with the introduction of mechanised mowing machines.

Norris worked out that not only were the mowing machines killing chicks as they cut the grass for hay, farmers were using them earlier in the year, depriving corncrakes of the time they needed to fledge their chicks or have second broods.

Slowly, but surely, the bird disappeared, until they were only left in those parts of the country where farmers had not advanced the grass-cutting dates as much as elsewhere. This was particularly true in the machair grasslands of islands such as Tiree and much of the Outer Hebrides, because farmers allow it to grow long for hay or silage, and it provides perfect cover for corncrakes.

But still, until the implementation of a subsidy system in the 1990s, corncrakes continued to decline, even in the machairs. Then, farmers were paid to hold off cutting their grass, thus giving the females more time to raise their chicks and even have a second brood.

The corncrake in history and culture

The 19th-century English poet John Clare eulogised the strange and ubiquitous call of the corncrake in The Landrail, while there is a more lascivious Scottish folk song about the meeting of two young lovers on the banks of the River Doon in Ayr, where “the echo mocks the corncrakes among the

whinny knowes”.

Stanley Baldwin, pillar of the establishment and Prime Minister on three occasions in the 1920s and 30s, described “the corncrake on a dewey morning” as one of the sounds of England, along with “the tinkle of hammer on anvil in the country smithy and the scythe against the whetstone”.